Analysis: How did Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

From the evidence provided in Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island? it is clear that Mary Ann had no involvement in Fred Ward’s abscondment on 11 September 1863 or his subsequent escape from Cockatoo Island. Did anyone else help him and his accomplice, Fred Britten?

Letters to and from prisoners were read by the Cockatoo Island authorities who were also present during all prisoner visits. This made it extremely difficult for escape plans to be communicated by letter or in person, so it is not surprising that most escape attempts were either the product of spur-of-the-moment decisions based on unexpectedly fortuitous circumstances, or plans that self-evidently originated on the island. Most focussed upon hiding on the island for an extended period of time, long enough that the authorities would give up the search and stand down the patrols – at which point the escapees would take to the water.

The Daily State of the Establishment reveals that Fred Ward had no visitors between his return to Cockatoo Island in 1861 and June 1863 when the register ends, whereas during his previous stint on Cockatoo Island he had received a number of visitors. Fred Britten received two visitors between February and June 1863: a John Ellis in March who was possibly a relative, and a ‘Mr Lane’ in May – probably a lawyer or government official as titles such as “Mr” were seemingly given only to official visitors to the island.[1]

Unfortunately, the Daily State of the Establishment volume covering the period from July 1863 to 1866 has not survived, so visitor details cannot be determined. However official correspondence makes no reference to possible external assistance, so it seems unlikely that anyone visited either of the men in the ten weeks prior to their escape otherwise the Superintendent would undoubtedly have requested that the authorities question these visitors.[2] For all of these reasons, it seems highly unlikely that Ward and Britten had outside help.

The pair evidently found an ideal hiding place and remained there for a couple of days. Later references to Fred’s escape (secondary-source references) mention his supposed hiding place, however, as these refer only to Fred himself and ignore the fact that he had a companion, doubts must arise as to whether these references are true. For example, Inspector Langworthy said that Mary Ann Bugg told him that Fred hid in a disused boiler.[3] But, since the other parts of this story are clearly untrue (see Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?), we have to conclude that this entire claim is problematic – including the suggestion that Fred hid in a disused boiler.

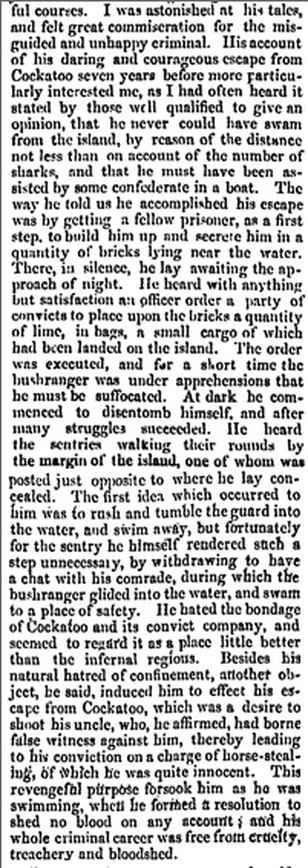

Another account of Fred’s escape was published in the Armidale Telegraph shortly after Fred’s demise (see photocopy below).[4] These Recollections of Thunderbolt were provided by a bushman who had reportedly spent an evening in Fred’s company sometime previously. The stories recounted by the bushman distinctly resemble documented events involving Thunderbolt, yet with the slight differences that occur when a story has been embellished by the speaker and is being recounted at a later date by the listener. These slight differences, oddly enough, suggest that the bushman was telling the truth. Detectives know, for example, that if multiple witness accounts exactly match each other they are likely to be the product of “coaching”. Similarly, if the bushman’s stories exactly matched the newspaper reports they were likely to have been the result of study rather than conversation. If they bore no resemblance to other sources at all, they would be of doubtful authenticity because they could not be substantiated. So, before recounting the bushman’s story of Fred’s escape from Cockatoo Island, let us examine the other stories Fred reportedly told him (for the full article, see Online Newspapers):

1. The bushman said that Fred talked about an encounter at the Rocks, at Uralla, “where the police, under Sergeant Granger, attacked him and his mate and wounded him”, and that “his horse got bogged and he limped away on foot, the police not daring to follow him”. False stories, like the claims that Fred escaped to America and died in Canada, rarely include specifics because these can be checked out. However the specificity of the name Sergeant Granger combined with the references to Fred having a companion at that time, his own wounding and the bogged horse all match the contemporary accounts.

2. Fred also reportedly mentioned that he had been “hard pressed at times, particularly on one occasion by a constable named Dalton, at Tamworth, who, he said, was a brave man”. Dalton was from the Tamworth police station and participated in the Millie gunfight in April 1865 when Fred’s young accomplice, John Thompson, was shot (see Timeline: 1865 – First gang). Dalton also nearly captured Fred and a later accomplice, Thomas Mason, in the Borah Ranges in August 1867 (see Timeline: 1867), and a couple of weeks later the police forced Fred and his young companion to separate, leading to Mason’s apprehension. Dalton, of all the policemen on Fred’s tail, had nearly caught him twice, had shown his own bravery in the process, had wounded Thompson forcing Fred’s first gang to be disbanded, and had contributed to the break-up of his partnership with young Mason and the lad’s subsequent capture. That Fred should reportedly have commented on the activities and bravery of Dalton, of all policemen, strongly suggests that the bushman was repeating Fred’s comments. This is not the sort of thing that the ordinary person would remember simply from reading newspaper articles over a period of years – and old articles could not easily be checked in those days. Even I (having written about Thunderbolt) had to search for my references to Dalton to see why Fred would have commented on his endeavours; I discovered that he was indeed a policeman who was worthy of Fred’s praise.

3. Fred also told the story of “some gentleman in New England who had made a boast that he would shoot him the first time that he met him” and how he later met the man and introduced himself, and took the man’s revolver and gold watch, and the man was scared but Fred reassured him and rode many miles with him. This was almost certainly Magistrate Hugh Bryden of the Collarenebri district (rather than the New England district, one of the slight errors mentioned), whose encounters with Fred are covered in Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady (see also the Timelines for 1865).

4. Another story told how Fred and a young protégé stuck up a public-house. The innkeeper (whom he names Boniface) made a desperate leap and seized him by the arms preventing him from using his revolver, however the inn’s customers did not come to the man’s assistance. Fred called out to his accomplice to use his knife and “let his bowels out” and, seeing the unsheathed knife, the innkeeper released his hold and ran for shelter. Fred said that this was his narrowest escape from capture. Apart from the fact that the attacker was a customer named McInnes rather than the innkeeper (whose name was Simpson), the rest of the tale is true (see Timeline: 1867 for sources). It was indeed Fred’s closest shave with capture. In fact, this story provides incredibly strong evidence that the bushman did indeed hear Fred's reminiscences. In reporting the Simpson robbery, the newspapers stated: "a person named McGuiness (sic) came in and seeing how matters stood seized Thunderbolt ... [and] from some cause not explained, the man who had hold of Thunderbolt immediately bolted". Many newspapers repeated this report but none provided any explanation for McInnes' sudden decision to bolt. However the depositions at Mason's committal late in 1867 provided the explanation. Victim Charles McKenzie swore under oath: "I saw a man named McInnes ... seize prisoner's companion [Ward] who then called out to the prisoner [Mason] to use his knife and rip McInnis' belly open." Mason pleaded guilty at his eventual trial so the witnesses did not testify. Accordingly it seems highly unlikely that these words were published in any press reports, so the only way the bushman could have known of the reason – and provided an almost verbatrim description of the dramatic words used – is if he heard it from someone with a personal knowledge of the event.

All of these stories are documented in contemporary records, yet all of the bushman’s accounts contain the slight errors that are found in second-hand repetitions at a later date. On the grounds that the likely accuracy of unverifiable information can be determined by the accuracy of verifiable information, all of these stories receive ticks suggesting the veracity of the man providing the Recollections. One can state with a high degree of certainty that the bushman did indeed meet Fred and that Fred did indeed recount his adventures.

Which brings up to the bushman's statement regarding Fred's escape from Cockatoo Island (see below):[4]

The problem with the bushman’s account is that he doesn’t mention Britten. Could Ward and Britten have hidden in different places? This seems unlikely as they would have required two excellent hiding places. Many of the clever hiding places used by absconders existed only because of particular circumstances at the time – building operations, for example – and the non-transient hiding places were undoubtedly searched the next time an escape attempt was made. Moreover, if they had hidden in separate places, the odds of finding them would have doubled. If they had indeed found separate hiding places then they probably would have swum from the island at separate times. They were safer apart than together, so there would be no reason for them to try to meet up again at a later date. As it was, they apparently swam from the island together, journeyed to the New England district together, and separated two months after their escape.

What about the claim that a fellow prisoner built up a stack of bricks around Fred (or perhaps around both of them)? To do so, the prisoner would have had to use wooden beams to support the brick structure so that it wouldn’t fall on Fred. Hiding one man as they built such a stack would be difficult; hiding two men even more problematic. Could the story be true? The authenticity of the other stories suggests that this story could indeed be authentic – except for the fact that it only mentions Fred Ward and describes an unlikely hiding place. The jury is still out.

The story continued that Fred escaped the same night, whereas the evidence shows that the pair escaped two days after they absconded. But this is a minor error, the sort that could easily be made in a second-hand recounting of the story sometime afterwards.

Most Thunderbolt books claim that Ward and Britten swam to Balmain after escaping from the island. Yet, according to the Superintendent’s reports at the time of the escape, part of their clothing and Britten’s irons were found together, and some more of Britten's clothing in the water on the north side of the island opposite Woolwich. Upon this discovery, the superintendent immediately sent guards to the North Shore to search for them. The distance from the island’s north side to Woolwich was shorter than the distance from the south side to Balmain, Moreover, the night of the 13/14 September 1863 was starlit, and sentries were stationed around the island.[5] If the escapees entered the water on the north side of the island, as seems almost certain, why would they swim south to Balmain? To do so, they would need to swim half way around the island, risking being heard or seen, then across to Balmain. Moreover, such an extensive period in the water would have put them at greater risk of a shark attack and at the mercy of the tides and undercurrents. Alternatively, from the north side, they had only a short swim to the less-populated Woolwich area.

W.G. Small, a gaol superintendent at Berrima from 1861 to 1869, wrote in his reminiscences that an old lady who had once lived at Lane Cove told him that Ward arrived at her place and was so wet and cold that she took pity on him and supplied him with food and clothes but never told anyone for “fear of the consequences”.[6] This story seems feasible although it is again weakened by the fact that it makes no mention of Ward’s companion.

To date, all we know with certain about Ward and Britten’s escape is the following:

- That they absconded at the same time and from the same gang on the afternoon of 11 September 1863;

- That they probably hid together on the island;

- That they seemingly swam together from Cockatoo island on the night of 13/14 September 1863;

- That they seemingly swam north to Woolwich;

- That they headed north to the New England district, probably via the Gloucester district;

- That they were still together in the New England district in early November 1863;

- That they separated around mid-November 1863.

Perhaps with more newspapers becoming available online, we might one day discover more information about Ward and Britten's singular escape from Cockatoo Island.

What about the claim that a fellow prisoner built up a stack of bricks around Fred (or perhaps around both of them)? To do so, the prisoner would have had to use wooden beams to support the brick structure so that it wouldn’t fall on Fred. Hiding one man as they built such a stack would be difficult; hiding two men even more problematic. Could the story be true? The authenticity of the other stories suggests that this story could indeed be authentic – except for the fact that it only mentions Fred Ward and describes an unlikely hiding place. The jury is still out.

The story continued that Fred escaped the same night, whereas the evidence shows that the pair escaped two days after they absconded. But this is a minor error, the sort that could easily be made in a second-hand recounting of the story sometime afterwards.

Most Thunderbolt books claim that Ward and Britten swam to Balmain after escaping from the island. Yet, according to the Superintendent’s reports at the time of the escape, part of their clothing and Britten’s irons were found together, and some more of Britten's clothing in the water on the north side of the island opposite Woolwich. Upon this discovery, the superintendent immediately sent guards to the North Shore to search for them. The distance from the island’s north side to Woolwich was shorter than the distance from the south side to Balmain, Moreover, the night of the 13/14 September 1863 was starlit, and sentries were stationed around the island.[5] If the escapees entered the water on the north side of the island, as seems almost certain, why would they swim south to Balmain? To do so, they would need to swim half way around the island, risking being heard or seen, then across to Balmain. Moreover, such an extensive period in the water would have put them at greater risk of a shark attack and at the mercy of the tides and undercurrents. Alternatively, from the north side, they had only a short swim to the less-populated Woolwich area.

W.G. Small, a gaol superintendent at Berrima from 1861 to 1869, wrote in his reminiscences that an old lady who had once lived at Lane Cove told him that Ward arrived at her place and was so wet and cold that she took pity on him and supplied him with food and clothes but never told anyone for “fear of the consequences”.[6] This story seems feasible although it is again weakened by the fact that it makes no mention of Ward’s companion.

To date, all we know with certain about Ward and Britten’s escape is the following:

- That they absconded at the same time and from the same gang on the afternoon of 11 September 1863;

- That they probably hid together on the island;

- That they seemingly swam together from Cockatoo island on the night of 13/14 September 1863;

- That they seemingly swam north to Woolwich;

- That they headed north to the New England district, probably via the Gloucester district;

- That they were still together in the New England district in early November 1863;

- That they separated around mid-November 1863.

Perhaps with more newspapers becoming available online, we might one day discover more information about Ward and Britten's singular escape from Cockatoo Island.

Sources:

[1] Cockatoo Island – Daily State of the Establishment, 1861-63 [SRNSW ref: 4/6505]

[2] Cockatoo Island – Letter Book: Re Ward & Britten [SRNSW 4/6518 pp.154-160]

[3] Macleod, Alton Richmond The Transformation of Manellae: A History of Manilla, A.R. Macleod, Manilla, 1949, p.23

[4] Recollections of Thunderbolt originally published in Armidale Telegraph and repeated in Argus 24 Aug 1870 p.7; the above photocopy is copy taken from West Coast Times, 28 Sep 1870 p.3 (a New Zealand paper that laid out the whole Cockatoo Island section in the one column)

[5] Cockatoo Island – Letter Book: Re Ward & Britten [SRNSW ref: 4/6518 pp.154-160]

[6] Small, W.G. Reminiscences of Gaol Life at Berrima, A.K Murray & Co, Paddington (NSW), c1923, p.6

[1] Cockatoo Island – Daily State of the Establishment, 1861-63 [SRNSW ref: 4/6505]

[2] Cockatoo Island – Letter Book: Re Ward & Britten [SRNSW 4/6518 pp.154-160]

[3] Macleod, Alton Richmond The Transformation of Manellae: A History of Manilla, A.R. Macleod, Manilla, 1949, p.23

[4] Recollections of Thunderbolt originally published in Armidale Telegraph and repeated in Argus 24 Aug 1870 p.7; the above photocopy is copy taken from West Coast Times, 28 Sep 1870 p.3 (a New Zealand paper that laid out the whole Cockatoo Island section in the one column)

[5] Cockatoo Island – Letter Book: Re Ward & Britten [SRNSW ref: 4/6518 pp.154-160]

[6] Small, W.G. Reminiscences of Gaol Life at Berrima, A.K Murray & Co, Paddington (NSW), c1923, p.6