Analysis:

What did William Monckton say about Thunderbolt?

Copyright Carol Baxter 2011

The Empire 1 Jun 1870 p.2

Thunderbolt aficionados who insist that Frederick Ward was not the bushranger shot near Uralla on 25 May 1870 often use the contradictory statements made by Fred’s accomplice, William Monckton, to support their claims. It is important, therefore, to examine these statements to see what Monckton actually said.

The year 1870

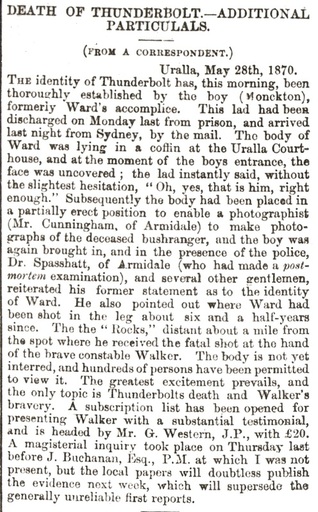

Purely by chance, Monckton arrived on the mail coach from Sydney two days after the bushranger was shot. The following day, he was taken to view the body which was on display in the Uralla courthouse. A local correspondent reported that Monckton instantly identified the dead bushranger as being Fred Ward. “Oh, yes, that is him, right enough,” Monckton said (see adjacent newspaper report). He also pointed out where Fred had been shot at "the Rocks" (now known as Thunderbolt's Rock) six-and-a-half-years previously.[1]

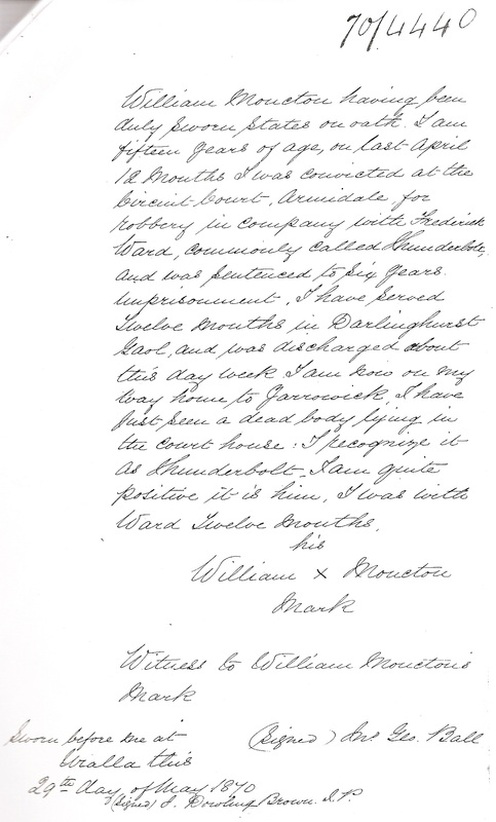

Monckton signed a sworn statement to that effect – that is, he swore a legally binding oath declaring that his statement was the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth – as shown below. This statement was sent with the police reports to the Inspector General of Police in Sydney, on 30 May 1870 and ultimately ended up in the records of the NSW Colonial Secretary.[2]

The year 1870

Purely by chance, Monckton arrived on the mail coach from Sydney two days after the bushranger was shot. The following day, he was taken to view the body which was on display in the Uralla courthouse. A local correspondent reported that Monckton instantly identified the dead bushranger as being Fred Ward. “Oh, yes, that is him, right enough,” Monckton said (see adjacent newspaper report). He also pointed out where Fred had been shot at "the Rocks" (now known as Thunderbolt's Rock) six-and-a-half-years previously.[1]

Monckton signed a sworn statement to that effect – that is, he swore a legally binding oath declaring that his statement was the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth – as shown below. This statement was sent with the police reports to the Inspector General of Police in Sydney, on 30 May 1870 and ultimately ended up in the records of the NSW Colonial Secretary.[2]

____________________________________________________________________________

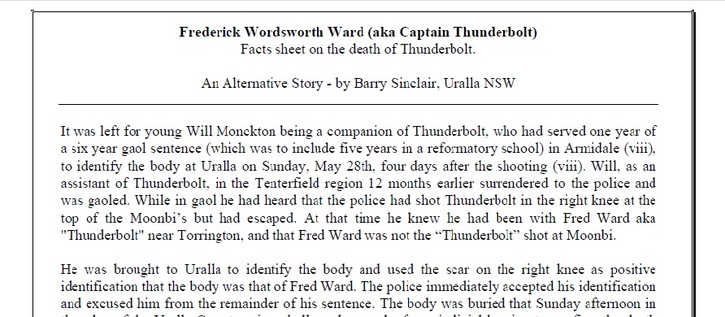

Yet those who claim that Thunderbolt did not die in 1870 also provide a quite different account of Monckton's identification of the dead body, as shown below:[3]

Yet those who claim that Thunderbolt did not die in 1870 also provide a quite different account of Monckton's identification of the dead body, as shown below:[3]

The "Facts sheet" author states that Monckton had served a year of his sentence in Armidale and was brought from there to identify the body. Yet both Monckton himself and The Empire state that he had served his time in Sydney, statements supported by official records.[4] The Facts sheet author also writes that Monckton identified the body on Sunday 28 May 1870, four days after the shooting, whereas Monckton identified the body on Saturday 28 May, three days after the shooting, and signed his statement on Sunday 29 May.

The author writes that "while in gaol [Monckton] had heard that the police had shot Thunderbolt in the right knee at the top of Moonbi's" but that Monckton knew that "Fred Ward was not the 'Thunderbolt' shot at Moonbi" as he was with Fred at that time. Yet neither contemporary newspapers nor issues of the Police Gazette report that Thunderbolt had been shot in the right knee at Moonbi or anywhere else. The author then writes that Monckton used the scar on the body's right knee as positive identification that it was Fred Ward – intimating that Monckton was falsely identifying the dead bushranger as "Fred Ward" all the while knowing that the right-knee scar meant that it couldn't be Fred Ward.

What right-knee scar? Dr Spasshatt, who performed the post mortem examination, described the bushranger's body in great detail at the magisterial inquiry held on 26 May, testifying under oath to the presence of only one old scar: that found on the dead bushranger's left knee (see When did Frederick Ward die?). And Spasshatt was present when Monckton pointed out the injury to the bushranger's leg, the injury that Monckton himself said Fred received at the Rocks all those years previously. Clearly Monckton was identifying the body by the scar on the left knee. That being the case, the author's claim about the existence of a right-knee scar is evidently false.

The author then says that, as a consequence of Monckton's identification, the police released him from the rest of his sentence – intimating that this was a payment for services rendered. In fact, Monckton had already been released from gaol in Sydney. His trial judge had sentenced him to one year in gaol then five years in a Reformatory School but as no Reformatory School existed, the authorities authorised his discharge, although his return to the Armidale district was delayed because of ill health.[4]

____________________________________________________________________________

The year 1905

Thirty-five years after Frederick Ward's death, author Ambrose Platt decided to turn Monckton's adventures into a dramatic novel Three Years with Thunderbolt (many incorrectly believe it to be a memoir and quote it accordingly yet even the title itself reveals that Monckton's recollections have been embellished as he in fact roamed with Fred Ward for only eleven months).[5] What does the book say about the identity of Monckton's bushranging mentor? The book carried the subtitle: "Being the narrative of William Monckton, who for three years attended the famous outlaw, Frederick Ward, better known as Captain Thunderbolt ..." And the last sentence of the book indirectly confirms that Thunderbolt was Fred Ward: "I never saw Thunderbolt again, for when next I looked upon his face, he had been for many hours a corpse."

Clearly, the fifty-year-old Monckton knew that he had once roamed with Fred Ward and that the dead body he was asked to identify was that of his bushranging mentor, Fred Ward.

The year 1937

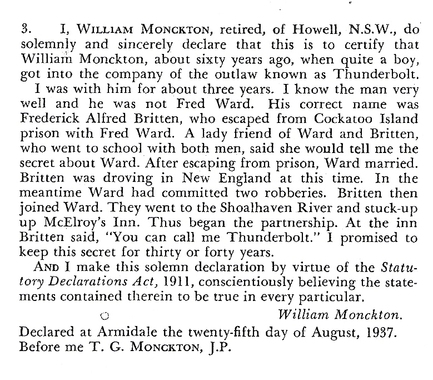

Another novelist latched onto Thunderbolt's story in the mid-1930s: Annie Rixon reportedly paid Monckton a visit and stayed for six months.[6] On 25 August 1937, Monckton signed the following Statutory Declaration at Rixon's behest:[7]

The author writes that "while in gaol [Monckton] had heard that the police had shot Thunderbolt in the right knee at the top of Moonbi's" but that Monckton knew that "Fred Ward was not the 'Thunderbolt' shot at Moonbi" as he was with Fred at that time. Yet neither contemporary newspapers nor issues of the Police Gazette report that Thunderbolt had been shot in the right knee at Moonbi or anywhere else. The author then writes that Monckton used the scar on the body's right knee as positive identification that it was Fred Ward – intimating that Monckton was falsely identifying the dead bushranger as "Fred Ward" all the while knowing that the right-knee scar meant that it couldn't be Fred Ward.

What right-knee scar? Dr Spasshatt, who performed the post mortem examination, described the bushranger's body in great detail at the magisterial inquiry held on 26 May, testifying under oath to the presence of only one old scar: that found on the dead bushranger's left knee (see When did Frederick Ward die?). And Spasshatt was present when Monckton pointed out the injury to the bushranger's leg, the injury that Monckton himself said Fred received at the Rocks all those years previously. Clearly Monckton was identifying the body by the scar on the left knee. That being the case, the author's claim about the existence of a right-knee scar is evidently false.

The author then says that, as a consequence of Monckton's identification, the police released him from the rest of his sentence – intimating that this was a payment for services rendered. In fact, Monckton had already been released from gaol in Sydney. His trial judge had sentenced him to one year in gaol then five years in a Reformatory School but as no Reformatory School existed, the authorities authorised his discharge, although his return to the Armidale district was delayed because of ill health.[4]

____________________________________________________________________________

The year 1905

Thirty-five years after Frederick Ward's death, author Ambrose Platt decided to turn Monckton's adventures into a dramatic novel Three Years with Thunderbolt (many incorrectly believe it to be a memoir and quote it accordingly yet even the title itself reveals that Monckton's recollections have been embellished as he in fact roamed with Fred Ward for only eleven months).[5] What does the book say about the identity of Monckton's bushranging mentor? The book carried the subtitle: "Being the narrative of William Monckton, who for three years attended the famous outlaw, Frederick Ward, better known as Captain Thunderbolt ..." And the last sentence of the book indirectly confirms that Thunderbolt was Fred Ward: "I never saw Thunderbolt again, for when next I looked upon his face, he had been for many hours a corpse."

Clearly, the fifty-year-old Monckton knew that he had once roamed with Fred Ward and that the dead body he was asked to identify was that of his bushranging mentor, Fred Ward.

The year 1937

Another novelist latched onto Thunderbolt's story in the mid-1930s: Annie Rixon reportedly paid Monckton a visit and stayed for six months.[6] On 25 August 1937, Monckton signed the following Statutory Declaration at Rixon's behest:[7]

The Statutary Declaration indicates that Monckton had changed his story. That being the case, the first thing to ask is how reliable is this Declaration? When we apply the historical detection tool of attempting to determine the likely accuracy of unknown information by assessing the accuracy of known information, we immediately encounter problems. Monckton in his Declaration says that he became Thunderbolt's companion about "sixty years ago". In fact it was seventy years previously. He also said he was with Thunderbolt "for about three years". In fact, it was only eleven months.

A Statutory Declaration is a legally binding document signed under oath and attesting to the fact that the signatory is stating the truth. To begin his Statutory Declaration with such untruths indicates that Monckton was either lying or confused or forgetful. Notably, he was in his eighties when he signed the 1937 Declaration.

However let’s ignore the issue of the Declaration’s questionable reliability for the moment and look at Monckton’s actual statements. Firstly, he makes no reference to the man who died in 1870, or to the death of anyone at all. His purpose was to say that Thunderbolt was not Fred Ward but was instead Ward’s fellow Cockatoo Island escapee Fred Britten.

Secondly, he says that "A lady friend of Ward and Britten, who went to school with both men, said she would tell me the secret about Ward." He then recounts some information about the pair and concludes: "I promised to keep this secret for thirty or forty years." It is important to note that this information clearly did not come from Ward himself, or from Britten, or from whomever Monckton thought Thunderbolt was by the time he was in his dotage. The information came from this unnamed "lady friend". Her "secret about Ward" was that Ward was actually Britten. Clearly this unnamed lady was responsible for convincing Monckton that the man he had accompanied for nearly a year and had, until then, declared to be Fred Ward was in actual fact Fred Britten. It was her information he had reportedly promised to keep secret for 30 or 40 years, not Ward’s or Britten’s.

But there are serious problems with this information.

1. The lady said she went to school with Ward and Britten. If Ward attended school, it was at Windsor. Britten himself said that he was born in Tasmania and arrived in New South Wales in 1845[8], around the time that Fred began droving, so on those grounds alone this information cannot be correct. Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest that Ward and Britten ever met prior to their incarceration on Cockatoo Island.

2. The lady’s information intimates that Ward and Britten escaped from Cockatoo Island, went their separate ways, then joined together again and committed some robberies down south in the Shoalhaven district. In fact, they remained together for a couple of months after their escape from Cockatoo Island, committed robberies up north in the New England district, then split up.[9]

3. The lady reported that the pair robbed McElroy’s Inn at the Shoalhaven, presumably late in 1863 or 1864. The Police Gazettes for 1863 and 1864 do not mention a robbery of a man named McElroy anywhere in NSW (by that spelling or any other). The Government Gazette for 1865 does not include a McElroy at Shoalhaven in its list of NSW innkeepers, nor does a Google search pick up any references to such an innkeeper.

Clearly, no supportive evidence has been found to back up the lady's "secret" information, as reported in Monckton’s 1937 Statutory Declaration. Conversely, strong evidence has been found to refute her claims.

Soon after Monckton signed this Statutory Declaration at Annie Rixon's behest, she produced a supposedly factual book claiming that Thunderbolt was Fred Britten rather than Fred Ward.[10] In fact, Rixon’s book is no more factual than Monckton’s Three Years with Thunderbolt (see Reviews). It seems likely that Monckton’s "memory" had been heavily influenced for the second time by a woman with an agenda – or perhaps the lady who convinced him that Thunderbolt was Britten rather than Ward was none other than Annie Rixon herself.

The year 1940

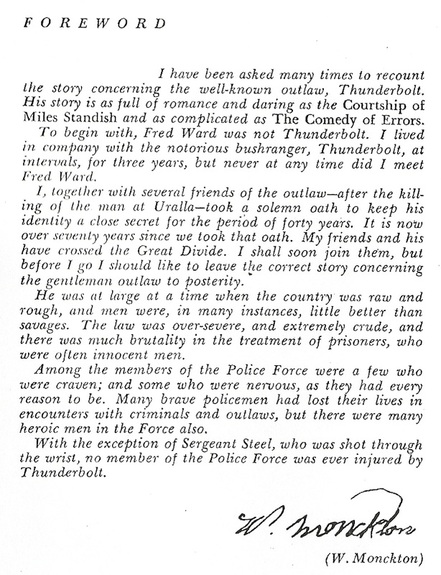

Monckton’s 1937 Statutory Declaration was included in Annie Rixon’s The Truth about Thunderbolt, published in 1940. This book also included a Foreword written by Monckton that states:

A Statutory Declaration is a legally binding document signed under oath and attesting to the fact that the signatory is stating the truth. To begin his Statutory Declaration with such untruths indicates that Monckton was either lying or confused or forgetful. Notably, he was in his eighties when he signed the 1937 Declaration.

However let’s ignore the issue of the Declaration’s questionable reliability for the moment and look at Monckton’s actual statements. Firstly, he makes no reference to the man who died in 1870, or to the death of anyone at all. His purpose was to say that Thunderbolt was not Fred Ward but was instead Ward’s fellow Cockatoo Island escapee Fred Britten.

Secondly, he says that "A lady friend of Ward and Britten, who went to school with both men, said she would tell me the secret about Ward." He then recounts some information about the pair and concludes: "I promised to keep this secret for thirty or forty years." It is important to note that this information clearly did not come from Ward himself, or from Britten, or from whomever Monckton thought Thunderbolt was by the time he was in his dotage. The information came from this unnamed "lady friend". Her "secret about Ward" was that Ward was actually Britten. Clearly this unnamed lady was responsible for convincing Monckton that the man he had accompanied for nearly a year and had, until then, declared to be Fred Ward was in actual fact Fred Britten. It was her information he had reportedly promised to keep secret for 30 or 40 years, not Ward’s or Britten’s.

But there are serious problems with this information.

1. The lady said she went to school with Ward and Britten. If Ward attended school, it was at Windsor. Britten himself said that he was born in Tasmania and arrived in New South Wales in 1845[8], around the time that Fred began droving, so on those grounds alone this information cannot be correct. Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest that Ward and Britten ever met prior to their incarceration on Cockatoo Island.

2. The lady’s information intimates that Ward and Britten escaped from Cockatoo Island, went their separate ways, then joined together again and committed some robberies down south in the Shoalhaven district. In fact, they remained together for a couple of months after their escape from Cockatoo Island, committed robberies up north in the New England district, then split up.[9]

3. The lady reported that the pair robbed McElroy’s Inn at the Shoalhaven, presumably late in 1863 or 1864. The Police Gazettes for 1863 and 1864 do not mention a robbery of a man named McElroy anywhere in NSW (by that spelling or any other). The Government Gazette for 1865 does not include a McElroy at Shoalhaven in its list of NSW innkeepers, nor does a Google search pick up any references to such an innkeeper.

Clearly, no supportive evidence has been found to back up the lady's "secret" information, as reported in Monckton’s 1937 Statutory Declaration. Conversely, strong evidence has been found to refute her claims.

Soon after Monckton signed this Statutory Declaration at Annie Rixon's behest, she produced a supposedly factual book claiming that Thunderbolt was Fred Britten rather than Fred Ward.[10] In fact, Rixon’s book is no more factual than Monckton’s Three Years with Thunderbolt (see Reviews). It seems likely that Monckton’s "memory" had been heavily influenced for the second time by a woman with an agenda – or perhaps the lady who convinced him that Thunderbolt was Britten rather than Ward was none other than Annie Rixon herself.

The year 1940

Monckton’s 1937 Statutory Declaration was included in Annie Rixon’s The Truth about Thunderbolt, published in 1940. This book also included a Foreword written by Monckton that states:

From the Foreword, we can discern the following:

1. Monckton clearly states in the second paragraph that “Fred Ward was not Thunderbolt”.

2. Monckton’s reference to “the outlaw” in the third paragraph is clearly a reference to “the notorious bushranger Thunderbolt” in the second paragraph, that is, to the outlaw bushranger Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward.

3. The phrase in the third paragraph “after the killing of the man at Uralla” is an aside that needs to be eliminated from the line of text if Monckton’s meaning is to be determined. That done, Monckton’s sentence reads “I, together with several friends of the outlaw, took a solemn oath to keep his identity a close secret for the period of forty years.” The phrase “his identity” is clearly a reference to the previously mentioned outlaw. Therefore, Monckton is saying that he took a solemn oath to keep the identity secret of the outlaw Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward.

4. If Monckton was intending to refer to the outlaw Thunderbolt in the above-mentioned aside, he would have written: “I, together with several friends of the outlaw – after he was killed at Uralla – took a solemn oath to keep his identity a close secret …” But instead Monckton wrote: “I, together with several friends of the outlaw – after the killing of the man at Uralla – took a solemn oath to keep his identity a close secret ...’ This is extremely important. Clearly, the reference to the man killed at Uralla is a reference to someone other than the outlaw Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward.

5. In the Foreword, Monckton does not identify Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward. But in the Statutory Declaration he says that Thunderbolt’s “correct name was Frederick Alfred Britten”. Therefore Monckton is saying that he is keeping Britten’s identity secret and that the man killed at Uralla was not Britten. At no point does he say that Fred Ward was not the man killed at Uralla.

6. Clearly, Monckton’s Declaration cannot be used to argue that Fred Ward did not die at Uralla. At best, the combination of Monckton’s Statutory Declaration and Foreword simply shows that he was a very confused old man.

After Monckton's Statutory Declaration was published in the various editions of Annie Rixon's Thunderbolt books, a man named Oliver Smith wrote to the Charleville Times: "As a lad I worked with Bill Monckton ... The statement that Thunderbolt was Frederick Britten is not right. Bill Monckton was fond of relating many of the daring deeds performed by Thunderbolt and himself, and always claimed his boss' proper name was Fred Ward." He was not alone in attempting to correct the record.

So can Monckton's statements truly be used as evidence to show that Fred Ward was not the bushranger shot near Uralla in 1870? Not at all.

1. Monckton clearly states in the second paragraph that “Fred Ward was not Thunderbolt”.

2. Monckton’s reference to “the outlaw” in the third paragraph is clearly a reference to “the notorious bushranger Thunderbolt” in the second paragraph, that is, to the outlaw bushranger Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward.

3. The phrase in the third paragraph “after the killing of the man at Uralla” is an aside that needs to be eliminated from the line of text if Monckton’s meaning is to be determined. That done, Monckton’s sentence reads “I, together with several friends of the outlaw, took a solemn oath to keep his identity a close secret for the period of forty years.” The phrase “his identity” is clearly a reference to the previously mentioned outlaw. Therefore, Monckton is saying that he took a solemn oath to keep the identity secret of the outlaw Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward.

4. If Monckton was intending to refer to the outlaw Thunderbolt in the above-mentioned aside, he would have written: “I, together with several friends of the outlaw – after he was killed at Uralla – took a solemn oath to keep his identity a close secret …” But instead Monckton wrote: “I, together with several friends of the outlaw – after the killing of the man at Uralla – took a solemn oath to keep his identity a close secret ...’ This is extremely important. Clearly, the reference to the man killed at Uralla is a reference to someone other than the outlaw Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward.

5. In the Foreword, Monckton does not identify Thunderbolt-who-was-not-Fred-Ward. But in the Statutory Declaration he says that Thunderbolt’s “correct name was Frederick Alfred Britten”. Therefore Monckton is saying that he is keeping Britten’s identity secret and that the man killed at Uralla was not Britten. At no point does he say that Fred Ward was not the man killed at Uralla.

6. Clearly, Monckton’s Declaration cannot be used to argue that Fred Ward did not die at Uralla. At best, the combination of Monckton’s Statutory Declaration and Foreword simply shows that he was a very confused old man.

After Monckton's Statutory Declaration was published in the various editions of Annie Rixon's Thunderbolt books, a man named Oliver Smith wrote to the Charleville Times: "As a lad I worked with Bill Monckton ... The statement that Thunderbolt was Frederick Britten is not right. Bill Monckton was fond of relating many of the daring deeds performed by Thunderbolt and himself, and always claimed his boss' proper name was Fred Ward." He was not alone in attempting to correct the record.

So can Monckton's statements truly be used as evidence to show that Fred Ward was not the bushranger shot near Uralla in 1870? Not at all.

Sources:

[1] The Empire 1 Jun 1870 p.2

[2] Bushranging medals file: William Monckton's statement, signed 29 May 1870 [SRNSW ref: 1/2326.2 File 76/2239 No. 70/4440]

[3] Fact Sheet on the Death of Thunderbolt, sighted 14 Jun 2011

[http://www.thunderboltsway.com.au/resources/thunderbolt_alternate.pdf]

[4] Paperwork associated with the convictions of youths William Monckton and William Meehan, 1869-1870 [SRNSW ref: 4/592 No. 70/2865]; Maitland Mercury 13 April 1869 p.2

[5] Three years with Thunderbolt - published in the Daily Telegraph daily from 2 September 1905; see also Monckton, William Three Years with Thunderbolt, Cassell, Melbourne, 1907

[6] Williams, Stephan A Ghost called Thunderbolt, Popinjay, Woden (ACT), 1987, p.154

[7] Rixon, Annie Captain Thunderbolt, printed for the author by Edwards & Shaw, c1950

[8] Sydney Gaol – Description Book: Frederick Britton, 1862 [SRNSW ref: 4/6309 Year 1862 No.2638; Reel 860]. However no trace of Fred Britten has been found in Tasmania or elsewhere. Indeed he just ‘appears’ in November 1862 then ‘disappears’ after his escape from Cockatoo Island. It seems likely that ‘Frederick Britten’ was an alias. This will be discussed elsewhere.

[9] See Timeline: 1863

[10] Rixon, Annie The Truth about Thunderbolt, Australia's "Robin Hood", George Dash, Sydney, 1940

[11] Oliver Smith to the Charleville Times, 29 December 1955, quoted in A Ghost called Thunderbolt, p. 157 (see [6] above)

[1] The Empire 1 Jun 1870 p.2

[2] Bushranging medals file: William Monckton's statement, signed 29 May 1870 [SRNSW ref: 1/2326.2 File 76/2239 No. 70/4440]

[3] Fact Sheet on the Death of Thunderbolt, sighted 14 Jun 2011

[http://www.thunderboltsway.com.au/resources/thunderbolt_alternate.pdf]

[4] Paperwork associated with the convictions of youths William Monckton and William Meehan, 1869-1870 [SRNSW ref: 4/592 No. 70/2865]; Maitland Mercury 13 April 1869 p.2

[5] Three years with Thunderbolt - published in the Daily Telegraph daily from 2 September 1905; see also Monckton, William Three Years with Thunderbolt, Cassell, Melbourne, 1907

[6] Williams, Stephan A Ghost called Thunderbolt, Popinjay, Woden (ACT), 1987, p.154

[7] Rixon, Annie Captain Thunderbolt, printed for the author by Edwards & Shaw, c1950

[8] Sydney Gaol – Description Book: Frederick Britton, 1862 [SRNSW ref: 4/6309 Year 1862 No.2638; Reel 860]. However no trace of Fred Britten has been found in Tasmania or elsewhere. Indeed he just ‘appears’ in November 1862 then ‘disappears’ after his escape from Cockatoo Island. It seems likely that ‘Frederick Britten’ was an alias. This will be discussed elsewhere.

[9] See Timeline: 1863

[10] Rixon, Annie The Truth about Thunderbolt, Australia's "Robin Hood", George Dash, Sydney, 1940

[11] Oliver Smith to the Charleville Times, 29 December 1955, quoted in A Ghost called Thunderbolt, p. 157 (see [6] above)