Biography:

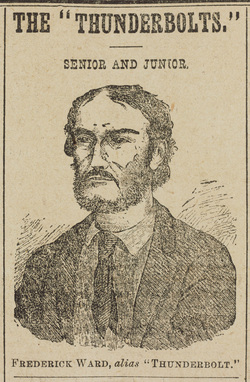

Bushranger Frederick Wordsworth Ward

alias Captain Thunderbolt

Copyright Carol Baxter 2011

From Truth 21 Feb 1892

Frederick Wordsworth Ward was the youngest of a large family of children born to Michael Ward (convict to New South Wales per Indefatigable 1815) and his wife Sophia[1]. Fred was born in 1835, around the time his family moved from Wilberforce, north of the Hawkesbury River, to Windsor on the south[2]. He spent his first decade at Windsor, where his parents probably paid for him to attend St Matthew's Church of England school as they had previously paid for his elder siblings to attend Wilberforce's church school[3]; however, similarly to some of his elder siblings, he later reported that he could read but not write[4]. Like most rural workers of the time, Fred was functionally illiterate.

In the mid-1840s, Fred's parents relocated to Maitland, west of Newcastle, where Michael died in 1859[5] and Sophia in 1874[6]. Fred had evidently spent time learning bush skills from his elder brothers as he was employed, at the age of eleven, as a "generally useful hand" by the owners of Aberbaldie station in the New England district. His first duty was to guide his new employers from Morpeth along the Great North Road to Aberbaldie station itself, an astonishing responsibility for a boy aged only eleven.[4]

During the following decade, Fred worked as a station hand, drover and horse-breaker at many stations in northern New South Wales, returning to spend time with his family at West Maitland between jobs. His many employers included Tocal station near Paterson in the Hunter Valley, the pre-eminent horse stud owned by Charles Reynolds.[4]

In March 1856, Fred offered to assist Tocal with a cattle muster and remained at the station for two weeks. In April 1856, some 45 horses were stolen from Tocal and neighbouring Bellevue stations; Bellevue, owned by William Zuill, suffered the largest loss. Soon afterwards, Fred was seen with two companions driving the stolen horses to Windsor. When asked about the horses, he directed the inquirers to his companion, his "master Mr Ross". His "master" was in fact his blackguard nephew, John Garbutt, who was responsible for stealing at least five mobs of horses and cattle in the northern districts in early 1856.[4] Clearly, Fred was no innocent victim of a dastardly plot, as some Thunderbolt writers like to claim.

John Garbutt pleaded guilty at Sydney's Supreme Court and was sentenced to ten years' servitude.[7] Fred and another nephew, James Garbutt, were tried at the Maitand Quarter Sessions on 13 August 1856. Fred was convicted of receiving stolen horses and James Garbutt of stealing horses. Both were sentenced to ten years hard labour and sent to the Cockatoo Island penal settlement where John Garbutt was already imprisoned.[4]

Fred behaved well. His only punishment was three days in the solitary confinement cells for falling asleep on the job while working as a night wardsman. In 1860, having completed only four years of his ten-year sentence, he and his two Garbutt nephews were released on tickets-of-leave (the colonial equivalent of a parole pass) to the Mudgee district. The conditions of their release included remaining in the Mudgee district and attending a muster every three months.[4]

The horse-stealing ringleader John Garbutt landed on his feet, marrying a wealthy and much older widow a few months after arriving in Mudgee, and settling at her inn and station at Cooyal.[7] Perhaps it was while attending their wedding that Fred met another Cooyal resident, a young part-Aboriginal woman named Mary Ann Bugg. She fell pregnant to Fred soon afterwards.[4]

For some reason, Fred decided to take Mary Ann back to her father's farm at Monkerai near Dungog for their baby's birth. After leaving her with her family, he galloped back to Mudgee but was late for his muster. As a punishment, he had his ticket-of-leave revoked. For riding into town on a "stolen" horse, he had another three years added to his sentence.[4]

Changes to penal regulations meant that Fred would have to serve the remaining six years of his first sentence plus the additional three years of his second sentence before he saw freedom again. Perhaps not surprisingly, Fred was one of the three dozen Cockatoo Island prisoners who rebelled against the changes in penal regulations early in 1863. Although sentenced to the solitary-confinement cells, he was not in fact sent down to their dank depths as there were not enough cells for all the rebels. Instead, he and his companions were locked in one of the prisoner wards. He was among a handful who continued to refuse to go back to work, ultimately spending 46 days locked in the wards until he gave up the battle. But his anger had not abated.[4]

On 11 September 1863, Fred and another prisoner, mail robber Frederick Brittain, absconded from their Cockatoo Island work station. On the morning of 14 September, some of their clothes and Brittain's irons were found by the water's edge on the island's northern shoreline (Fred Ward was not wearing irons at the time as he was not sentenced to wear irons). Apparently they swam north to Woolwich and not south to Balmain as many have since claimed.[4] Claims have also been made that they escaped with Mary Ann Bugg's assistance, but the records show that she was in fact working at Dungog at that time.[8]

The pair made their way to the New England district where, late in October 1863, they were spotted near the Big Rock (now Thunderbolt's Rock), south of Uralla. The police shot Fred in the back of the left knee but he managed to escape. He and Britten separated a few weeks later and Fred travelled south again to the Maitland district. On 22 December 1863, he robbed a toll-bar operator at Rutherford, west of Maitland, and afterwards informed his victim that his name was "Captain Thunderbolt".[9] The claim that Fred hammered on the tollkeeper's door, that the tollkeeper said, "By God, I thought it must have been a thunderbolt", and that Fred pointed a pistol at the innkeeper's head and said "I am the thunder and this my bolt", is merely part of the Thunderbolt mythology.

Soon afterwards, Fred collected Mary Ann and they headed for the lawless north-western plains where they remained quiet until early 1865.[10] Fred then joined forces with another three men, Thomas Hogan aka The Bull, McIntosh, and young John Thompson. They began a bushranging spree that ended when Thompson was shot at Millie in April 1865. The remaining gang members fled to Queensland and separated.[11]

Later in 1865, Fred joined forces with Patrick Kelly and Jemmy the Whisperer and began another bushranging spree in the north-western districts. At Carroll in December 1865, Jemmy shot but did not kill a policeman.[12]

The gang separated in January 1866 and Fred returned to Mary Ann, taking her back to the Gloucester district where they camped in the isolated mountains. Mary Ann was captured by the police in March 1866 and imprisoned on vagrancy charges but was released after a Parliamentary outcry.[13] Fred had a quiet year, only returning to bushranging early in 1867 after Mary Ann was again captured by the police and imprisoned.[14]

With a new accomplice, young Thomas Mason, Fred had another active year, robbing mails, inns and stores in the Tamworth and New England districts.[14] After Mason was captured in September 1867, Fred "eloped" with a young part-Aboriginal woman, Louisa Mason alias Yellow Long, who died of pneumonia near the Goulburn River west of Muswellbrook on 24 November 1867.[15] Fred returned to Mary Ann and, soon afterwards, she fell pregnant with their youngest child. They separated a short time later, never to be seen together again. Fred's namesake, Frederick Wordsworth Ward junior, was born in August 1868.[16]

Early in 1868, Fred took on another young accomplice, William Monckton, and had another busy bushranging year. They separated in December of that year and, a few weeks later, Monckton was also captured by the police.[17] During the following year-and-a-half, Fred ventured out on only half-a-dozen occasions. He was shot and killed at Kentucky Creek, near Uralla, on 25 May 1870.[18]

Claims that Frederick Ward was not shot at Kentucky Creek are merely part of the Thunderbolt mythology and are easily disproven.[19] In fact, claims that outlaw heroes "lived on" are a common ingredient in outlaw hero mythology, not merely in Australia but around the world, and are generally easy to disprove.[20]

Sources:

[1] See Analysis: Who were Frederick Ward's parents?

[2] See Analysis: When was Frederick Ward born? and Where was Frederick Ward born?

[3] See Timeline: Michael and Sophia Ward and their family

[4] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1835-1863

[5] See Death Certificate: Michael Ward (1859)

[6] See Death Certificate: Sophia Ward (1874)

[7] See John Garbutt

[8] See Analysis: Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

[9] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1863

[10] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1864

[11] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1865 - First gang

[12] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1865 - Second gang

[13] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1866

[14] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1867

[15] See Analysis: Did Mary Ann Bugg die in 1867?

[16] See Birth certificate: Frederick Wordsworth Ward (1868) and Baptism entry (1868)

[17] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1868

[18] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1870

[19] See Analysis: Did Frederick Ward die in 1870?

[20] Seal, Graham Outlaw Legend, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996

In the mid-1840s, Fred's parents relocated to Maitland, west of Newcastle, where Michael died in 1859[5] and Sophia in 1874[6]. Fred had evidently spent time learning bush skills from his elder brothers as he was employed, at the age of eleven, as a "generally useful hand" by the owners of Aberbaldie station in the New England district. His first duty was to guide his new employers from Morpeth along the Great North Road to Aberbaldie station itself, an astonishing responsibility for a boy aged only eleven.[4]

During the following decade, Fred worked as a station hand, drover and horse-breaker at many stations in northern New South Wales, returning to spend time with his family at West Maitland between jobs. His many employers included Tocal station near Paterson in the Hunter Valley, the pre-eminent horse stud owned by Charles Reynolds.[4]

In March 1856, Fred offered to assist Tocal with a cattle muster and remained at the station for two weeks. In April 1856, some 45 horses were stolen from Tocal and neighbouring Bellevue stations; Bellevue, owned by William Zuill, suffered the largest loss. Soon afterwards, Fred was seen with two companions driving the stolen horses to Windsor. When asked about the horses, he directed the inquirers to his companion, his "master Mr Ross". His "master" was in fact his blackguard nephew, John Garbutt, who was responsible for stealing at least five mobs of horses and cattle in the northern districts in early 1856.[4] Clearly, Fred was no innocent victim of a dastardly plot, as some Thunderbolt writers like to claim.

John Garbutt pleaded guilty at Sydney's Supreme Court and was sentenced to ten years' servitude.[7] Fred and another nephew, James Garbutt, were tried at the Maitand Quarter Sessions on 13 August 1856. Fred was convicted of receiving stolen horses and James Garbutt of stealing horses. Both were sentenced to ten years hard labour and sent to the Cockatoo Island penal settlement where John Garbutt was already imprisoned.[4]

Fred behaved well. His only punishment was three days in the solitary confinement cells for falling asleep on the job while working as a night wardsman. In 1860, having completed only four years of his ten-year sentence, he and his two Garbutt nephews were released on tickets-of-leave (the colonial equivalent of a parole pass) to the Mudgee district. The conditions of their release included remaining in the Mudgee district and attending a muster every three months.[4]

The horse-stealing ringleader John Garbutt landed on his feet, marrying a wealthy and much older widow a few months after arriving in Mudgee, and settling at her inn and station at Cooyal.[7] Perhaps it was while attending their wedding that Fred met another Cooyal resident, a young part-Aboriginal woman named Mary Ann Bugg. She fell pregnant to Fred soon afterwards.[4]

For some reason, Fred decided to take Mary Ann back to her father's farm at Monkerai near Dungog for their baby's birth. After leaving her with her family, he galloped back to Mudgee but was late for his muster. As a punishment, he had his ticket-of-leave revoked. For riding into town on a "stolen" horse, he had another three years added to his sentence.[4]

Changes to penal regulations meant that Fred would have to serve the remaining six years of his first sentence plus the additional three years of his second sentence before he saw freedom again. Perhaps not surprisingly, Fred was one of the three dozen Cockatoo Island prisoners who rebelled against the changes in penal regulations early in 1863. Although sentenced to the solitary-confinement cells, he was not in fact sent down to their dank depths as there were not enough cells for all the rebels. Instead, he and his companions were locked in one of the prisoner wards. He was among a handful who continued to refuse to go back to work, ultimately spending 46 days locked in the wards until he gave up the battle. But his anger had not abated.[4]

On 11 September 1863, Fred and another prisoner, mail robber Frederick Brittain, absconded from their Cockatoo Island work station. On the morning of 14 September, some of their clothes and Brittain's irons were found by the water's edge on the island's northern shoreline (Fred Ward was not wearing irons at the time as he was not sentenced to wear irons). Apparently they swam north to Woolwich and not south to Balmain as many have since claimed.[4] Claims have also been made that they escaped with Mary Ann Bugg's assistance, but the records show that she was in fact working at Dungog at that time.[8]

The pair made their way to the New England district where, late in October 1863, they were spotted near the Big Rock (now Thunderbolt's Rock), south of Uralla. The police shot Fred in the back of the left knee but he managed to escape. He and Britten separated a few weeks later and Fred travelled south again to the Maitland district. On 22 December 1863, he robbed a toll-bar operator at Rutherford, west of Maitland, and afterwards informed his victim that his name was "Captain Thunderbolt".[9] The claim that Fred hammered on the tollkeeper's door, that the tollkeeper said, "By God, I thought it must have been a thunderbolt", and that Fred pointed a pistol at the innkeeper's head and said "I am the thunder and this my bolt", is merely part of the Thunderbolt mythology.

Soon afterwards, Fred collected Mary Ann and they headed for the lawless north-western plains where they remained quiet until early 1865.[10] Fred then joined forces with another three men, Thomas Hogan aka The Bull, McIntosh, and young John Thompson. They began a bushranging spree that ended when Thompson was shot at Millie in April 1865. The remaining gang members fled to Queensland and separated.[11]

Later in 1865, Fred joined forces with Patrick Kelly and Jemmy the Whisperer and began another bushranging spree in the north-western districts. At Carroll in December 1865, Jemmy shot but did not kill a policeman.[12]

The gang separated in January 1866 and Fred returned to Mary Ann, taking her back to the Gloucester district where they camped in the isolated mountains. Mary Ann was captured by the police in March 1866 and imprisoned on vagrancy charges but was released after a Parliamentary outcry.[13] Fred had a quiet year, only returning to bushranging early in 1867 after Mary Ann was again captured by the police and imprisoned.[14]

With a new accomplice, young Thomas Mason, Fred had another active year, robbing mails, inns and stores in the Tamworth and New England districts.[14] After Mason was captured in September 1867, Fred "eloped" with a young part-Aboriginal woman, Louisa Mason alias Yellow Long, who died of pneumonia near the Goulburn River west of Muswellbrook on 24 November 1867.[15] Fred returned to Mary Ann and, soon afterwards, she fell pregnant with their youngest child. They separated a short time later, never to be seen together again. Fred's namesake, Frederick Wordsworth Ward junior, was born in August 1868.[16]

Early in 1868, Fred took on another young accomplice, William Monckton, and had another busy bushranging year. They separated in December of that year and, a few weeks later, Monckton was also captured by the police.[17] During the following year-and-a-half, Fred ventured out on only half-a-dozen occasions. He was shot and killed at Kentucky Creek, near Uralla, on 25 May 1870.[18]

Claims that Frederick Ward was not shot at Kentucky Creek are merely part of the Thunderbolt mythology and are easily disproven.[19] In fact, claims that outlaw heroes "lived on" are a common ingredient in outlaw hero mythology, not merely in Australia but around the world, and are generally easy to disprove.[20]

Sources:

[1] See Analysis: Who were Frederick Ward's parents?

[2] See Analysis: When was Frederick Ward born? and Where was Frederick Ward born?

[3] See Timeline: Michael and Sophia Ward and their family

[4] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1835-1863

[5] See Death Certificate: Michael Ward (1859)

[6] See Death Certificate: Sophia Ward (1874)

[7] See John Garbutt

[8] See Analysis: Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

[9] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1863

[10] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1864

[11] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1865 - First gang

[12] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1865 - Second gang

[13] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1866

[14] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1867

[15] See Analysis: Did Mary Ann Bugg die in 1867?

[16] See Birth certificate: Frederick Wordsworth Ward (1868) and Baptism entry (1868)

[17] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1868

[18] See Timeline: Frederick Ward 1870

[19] See Analysis: Did Frederick Ward die in 1870?

[20] Seal, Graham Outlaw Legend, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996