Analysis: When did Frederick Ward die?

The hoorah surrounding the subject of bushranger Fred Ward’s death is astonishing. Among the many claims and counter-claims, no one has suggested that Fred Ward died and rose again from the dead. Therefore, he either died on 25 May 1870 near Uralla or he didn’t. Evidence-based history requires scientific processes of analysis so let us boot out the oft-mentioned “I believes” and use scientific methodology to solve the problem once and for all.

First, let us reduce the problem to its simplest elements to help clarify the situation:

- A dead bushranger lying in Blanche's inn on 26 May 1870 needs a name;

- Two hypothetical people look at the dead body;

- One hypothetical person identifies the body as that of “Fred Ward”;

- The other hypothetical person says that the body is not that of “Fred Ward”.

So what, essentially, does this tell us?

- One of these two hypothetical people was telling the truth and the other was not telling the truth. Why? Because Fred Ward was either dead or alive. He could not be dead AND alive at the same time.

- Therefore the person who was telling the truth had knowledge or evidence that led them to reach their stated conclusion.

- Therefore the person who was not telling the truth was either ignorant, confused, in denial or deliberately lying.

But how do we determine who was telling the truth?

- By assessing the nature of the knowledge or evidence used to reach the conclusion.

Evidence can essentially be broken down into three types:

- Objective evidence obtained through observation, measurement or test, that is, evidence that anyone using the same strategies can locate or confirm for themselves. Today, forensic scientists use photographs, finger-prints, blood groups and DNA to identify individuals but in the past, before these scientific tools were available, the authorities used physical descriptions documented when a criminal was admitted to gaol – height, hair, eye and complexion colouring, and other distinctive features like tattoos, scars and moles. These were noted in Reward Notices when a criminal escaped custody. Objective evidence is the strongest type of evidence available.

- Subjective evidence that relies upon an individual’s personal knowledge and opinion. This type of information cannot be independently evaluated. For example, eye-witness identification is a form of subjective evidence.

- Circumstantial evidence that does not directly relate to the matter in question but points towards a specific conclusion.

So let us assess the evidence that led one hypothetical person to claim that the body was that of “Fred Ward”.

Circumstantial evidence

The following circumstantial evidence points in a certain direction:

- Fred Ward was a bushranger;

- Fred Ward’s bushranging territory specifically included the Uralla district where the dead man was shot, and Ward was known to be in the Armidale vicinity at that time;

- The dead man was a bushranger;

- Ergo, the dead man could be Fred Ward.

But:

- Circumstantial evidence is rarely strong enough to prove something beyond the shadow of a doubt; and

- Circumstantial evidence is usually considered weaker than subjective or objective evidence and must bow down before these stronger forms of evidence, if they are available.

Subjective evidence regarding the identification of the dead bushranger

- The two hypothetical people viewing the dead body are offering their opinions, therefore they are providing subjective evidence;

- One hypothetical person says the body is that of “Fred Ward” while the other says that it isn’t;

- As this subjective evidence contradicts itself, it effectively negates itself.

Objective evidence regarding the identification of the dead bushranger

At this point, we need to step away from the hypothetical claims and examine the actual evidence relating to the identity of the dead bushranger. On 26 May 1870 a magisterial inquiry was held at Uralla to identify the dead bushranger and determine his cause of death. The inquiry was held by Police Magistrate Buchanan and two Justices of the Peace were present. A special correspondent provided a verbatim report published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 1 June 1870.[1] Extracts from the report are included below. The full report can be examined online (see Online Newspapers).

First, let us reduce the problem to its simplest elements to help clarify the situation:

- A dead bushranger lying in Blanche's inn on 26 May 1870 needs a name;

- Two hypothetical people look at the dead body;

- One hypothetical person identifies the body as that of “Fred Ward”;

- The other hypothetical person says that the body is not that of “Fred Ward”.

So what, essentially, does this tell us?

- One of these two hypothetical people was telling the truth and the other was not telling the truth. Why? Because Fred Ward was either dead or alive. He could not be dead AND alive at the same time.

- Therefore the person who was telling the truth had knowledge or evidence that led them to reach their stated conclusion.

- Therefore the person who was not telling the truth was either ignorant, confused, in denial or deliberately lying.

But how do we determine who was telling the truth?

- By assessing the nature of the knowledge or evidence used to reach the conclusion.

Evidence can essentially be broken down into three types:

- Objective evidence obtained through observation, measurement or test, that is, evidence that anyone using the same strategies can locate or confirm for themselves. Today, forensic scientists use photographs, finger-prints, blood groups and DNA to identify individuals but in the past, before these scientific tools were available, the authorities used physical descriptions documented when a criminal was admitted to gaol – height, hair, eye and complexion colouring, and other distinctive features like tattoos, scars and moles. These were noted in Reward Notices when a criminal escaped custody. Objective evidence is the strongest type of evidence available.

- Subjective evidence that relies upon an individual’s personal knowledge and opinion. This type of information cannot be independently evaluated. For example, eye-witness identification is a form of subjective evidence.

- Circumstantial evidence that does not directly relate to the matter in question but points towards a specific conclusion.

So let us assess the evidence that led one hypothetical person to claim that the body was that of “Fred Ward”.

Circumstantial evidence

The following circumstantial evidence points in a certain direction:

- Fred Ward was a bushranger;

- Fred Ward’s bushranging territory specifically included the Uralla district where the dead man was shot, and Ward was known to be in the Armidale vicinity at that time;

- The dead man was a bushranger;

- Ergo, the dead man could be Fred Ward.

But:

- Circumstantial evidence is rarely strong enough to prove something beyond the shadow of a doubt; and

- Circumstantial evidence is usually considered weaker than subjective or objective evidence and must bow down before these stronger forms of evidence, if they are available.

Subjective evidence regarding the identification of the dead bushranger

- The two hypothetical people viewing the dead body are offering their opinions, therefore they are providing subjective evidence;

- One hypothetical person says the body is that of “Fred Ward” while the other says that it isn’t;

- As this subjective evidence contradicts itself, it effectively negates itself.

Objective evidence regarding the identification of the dead bushranger

At this point, we need to step away from the hypothetical claims and examine the actual evidence relating to the identity of the dead bushranger. On 26 May 1870 a magisterial inquiry was held at Uralla to identify the dead bushranger and determine his cause of death. The inquiry was held by Police Magistrate Buchanan and two Justices of the Peace were present. A special correspondent provided a verbatim report published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 1 June 1870.[1] Extracts from the report are included below. The full report can be examined online (see Online Newspapers).

|

Dr Spasshatt's testimony

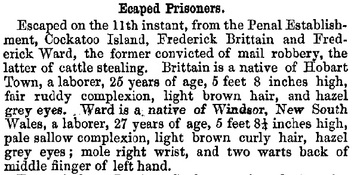

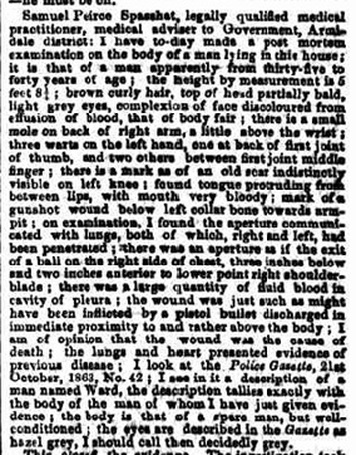

The Armidale medical adviser to the government, a legally qualified medical practitioner, examined the dead body and testified to the results of his examination (see adjacent newspaper report). In today’s terms, he is the forensic pathologist with the expert knowledge to make such an examination. During the post mortem examination, he noted down the body's physical features. He later compared these physical features with those listed in the Police Gazette after Fred Ward's escape from Cockatoo Island (see Escaped Prisoners notice below). In addition to height, hair and eye colouring and so on, the Police Gazette notice listed “mole right wrist, and two warts back of middle finger of left hand”. Note: the information in this Police Gazette notice is objective evidence observable to all which was provided by independent expert witnesses seven years prior to the bushranger’s death. In his testimony at the magisterial inquiry on 26 May, Dr Spasshatt testified that the dead body had "a small mole on back of right arm, a little above the wrist; three warts on the left hand, one at the back of first joint of thumb, and two others between first joint of middle finger". Note: this is also objective evidence provided by an independent expert witness. Spasshatt concludes that he compared his own description with the Police Gazette's description of Ward (shown below) and that "the description tallies exactly". John Blanche's testimony

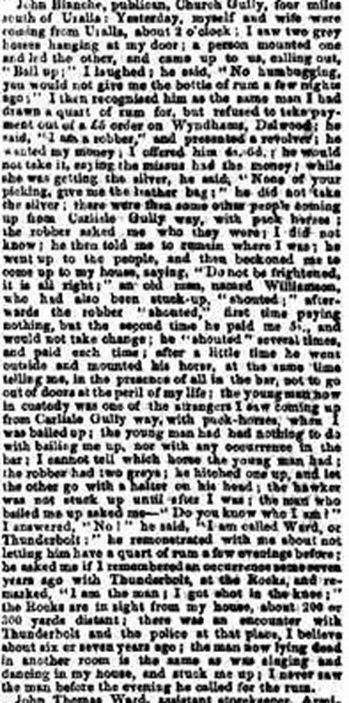

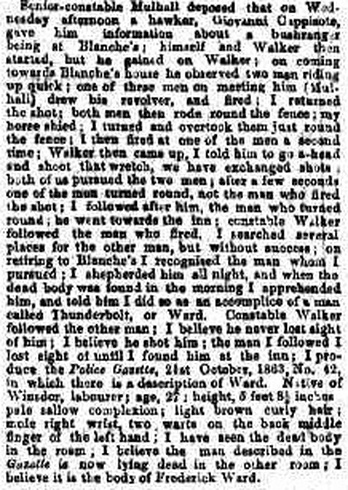

Publican John Blanche testified that the bushranger said to him (while drinking at the pub shortly before being shot): “I am called Ward, or Thunderbolt” and mentioned that he had been shot in the knee at the Rocks some seven years previously (see below). Blanche’s inn was built the year after Thunderbolt received this gunshot wound so Blanch himself was not resident there at the time of the encounter. Note: this is subjective evidence provided by someone with no vested interest in the outcome of the proceedings. John Mulhall's testimony

Senior Constable John Mulhall testified (see adjacent report) that he too compared the dead body with the Police Gazette notice. "I believe it is the body of Frederick Ward," he stated under oath. _________________________________________ |

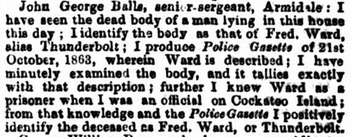

Sergeant Balls' testimony

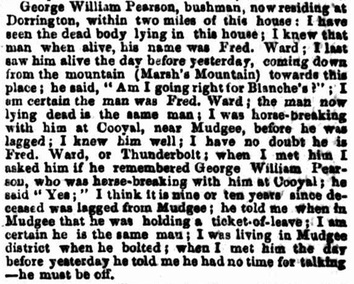

Sergeant John George Balls testified similarly (see below). He reported that he too had compared the dead body with the Escaped Prisoners notice (see adjacent) and had reached the same conclusion. Note: this is independent confirmation from an independent witness based upon objective evidence observable to all. Sergeant Balls also testified that he was stationed on Cockatoo Island when Fred Ward was incarcerated there[3], that he knew Fred personally, and that he could swear upon oath that the dead man was indeed Fred Ward. Note: this is subjective evidence provided by an independent "expert" witness so it is weighed as highly reliable in a court of law (unlike similar evidence provided by a gaol-house snitch, for example, who hopes to personally profit from testifying). George Pearson's testimony

George William Pearson testified (see below) that he had worked with Fred Ward at Mudgee ten years previously (in fact, he acted as Fred's defence witness at his 1861 trial – see Timeline: 1835-1863), that he had bumped into Ward on the day prior to the bushranger’s death, that the two of them had recognised each other, and that he could confirm that the dead body was indeed that of Fred Ward. This is subjective evidence provided by someone with the knowledge (independently-confirmed) to make such a claim, and who had no vested interest in the consequences of making such an identification. |

Verdict

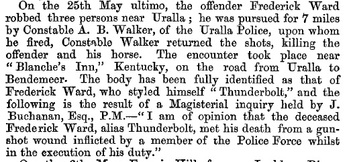

The result of the magisterial inquiry was announced in the Police Gazette on 1 Jun 1870: "a gunshot wound inflicted by a member of the Police Force whilst in the execution of his duty" (see above left). It is important to note that Magistrate Buchanan had reached this verdict two days before young William Monckton confirmed that the dead body was indeed that of Frederick Ward (see What did William Monckton actually say?). Monckton's identification was merely the cherry on top of the cake.

Conclusion:

This combination of objective and subjective evidence provided by witnesses testifying under oath in a court of law is, quite simply, the strongest type of evidence available. In the case of the dead bushranger lying in Uralla courthouse on 26 May 1870, the witnesses declared unequivocally that he was Cockatoo Island escapee Fred Ward.

So let us assess the evidence that led the other hypothetical person mentioned above to claim, on viewing the body, that it was not "Fred Ward":

- No one made such a claim! Yes, that’s correct. All the witnesses at the magisterial inquiry identified the dead body as that of Fred Ward. No one had any doubts whatsoever.

- And you too need have no doubts. You can read the Sydney Morning Herald's full report for yourself (see Sydney Morning Herald 1 Jun 1870 p.5 in the Online Newspapers). And you can read the Maitland Mercury's report (31 May 1870 p.2). And you can read all the other reports that are now available in the online newspapers if you search for the word "Thunderbolt" for the year 1870.

Thunderbolt survival stories

The rumours that Fred Ward “lived on” – that someone else's body inhabits Thunderbolt's Uralla grave – were not reported until many years later. So why did they surface at all when the evidence proves conclusively that Fred Ward died in 1870?

Graham Seal in his authoritative work The Outlaw Legend has determined that such survival stories are part of the world-wide outlaw hero mythology, the desperate need to believe that the outlaw hero ultimately triumphed over his adversaries despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Which brings us full-circle to the "I believe" claims. A person can believe whatever they want. But in this instance, the evidence clearly shows that Fred Ward was the bushranger shot near Uralla on 25 May 1870. So why are these claims still being made today?

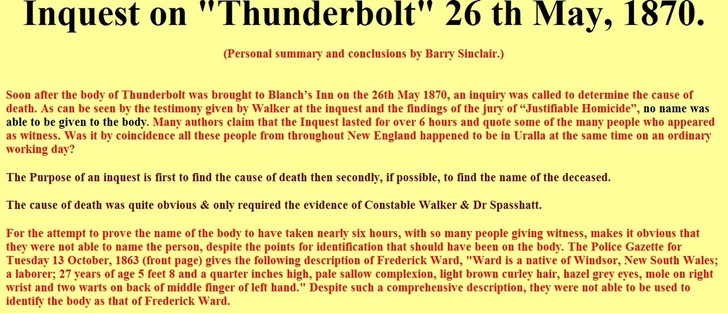

Let us examine some of these claims. In the folowing "Inquest "web-page, the author writes that, despite such a comprehensive description of Frederick Ward being provided in the Police Gazette for 1863, these details "were not able to be used to identify the body as that of Frederick Ward" (see below):[5]

The result of the magisterial inquiry was announced in the Police Gazette on 1 Jun 1870: "a gunshot wound inflicted by a member of the Police Force whilst in the execution of his duty" (see above left). It is important to note that Magistrate Buchanan had reached this verdict two days before young William Monckton confirmed that the dead body was indeed that of Frederick Ward (see What did William Monckton actually say?). Monckton's identification was merely the cherry on top of the cake.

Conclusion:

This combination of objective and subjective evidence provided by witnesses testifying under oath in a court of law is, quite simply, the strongest type of evidence available. In the case of the dead bushranger lying in Uralla courthouse on 26 May 1870, the witnesses declared unequivocally that he was Cockatoo Island escapee Fred Ward.

So let us assess the evidence that led the other hypothetical person mentioned above to claim, on viewing the body, that it was not "Fred Ward":

- No one made such a claim! Yes, that’s correct. All the witnesses at the magisterial inquiry identified the dead body as that of Fred Ward. No one had any doubts whatsoever.

- And you too need have no doubts. You can read the Sydney Morning Herald's full report for yourself (see Sydney Morning Herald 1 Jun 1870 p.5 in the Online Newspapers). And you can read the Maitland Mercury's report (31 May 1870 p.2). And you can read all the other reports that are now available in the online newspapers if you search for the word "Thunderbolt" for the year 1870.

Thunderbolt survival stories

The rumours that Fred Ward “lived on” – that someone else's body inhabits Thunderbolt's Uralla grave – were not reported until many years later. So why did they surface at all when the evidence proves conclusively that Fred Ward died in 1870?

Graham Seal in his authoritative work The Outlaw Legend has determined that such survival stories are part of the world-wide outlaw hero mythology, the desperate need to believe that the outlaw hero ultimately triumphed over his adversaries despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Which brings us full-circle to the "I believe" claims. A person can believe whatever they want. But in this instance, the evidence clearly shows that Fred Ward was the bushranger shot near Uralla on 25 May 1870. So why are these claims still being made today?

Let us examine some of these claims. In the folowing "Inquest "web-page, the author writes that, despite such a comprehensive description of Frederick Ward being provided in the Police Gazette for 1863, these details "were not able to be used to identify the body as that of Frederick Ward" (see below):[5]

They weren't?

As shown in the above newspaper reports, the magisterial inquiry (not inquest) conducted on 26 May 1870 by Police Magistrate Buchanan reached the verdict that the bushranger died of "a gunshot wound inflicted by a member of the Police Force whilst in the execution of his duty" (not "Justifiable Homicide") and that the dead body was that of bushranger Frederick Ward, or Thunderbolt.

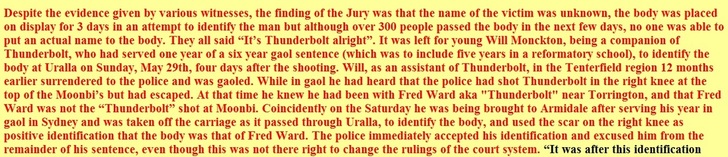

The author of the above "Inquest" web-page then claims that the body was not identified until William Monckton arrived at Uralla, that Monckton falsely identified the body as that of Fred Ward, and that the police illegally discharged him from the remainder of his sentence as a consequence, intimating that this discharge was authorised as a "payment" for identifying Ward (see below):[5]

As shown in the above newspaper reports, the magisterial inquiry (not inquest) conducted on 26 May 1870 by Police Magistrate Buchanan reached the verdict that the bushranger died of "a gunshot wound inflicted by a member of the Police Force whilst in the execution of his duty" (not "Justifiable Homicide") and that the dead body was that of bushranger Frederick Ward, or Thunderbolt.

The author of the above "Inquest" web-page then claims that the body was not identified until William Monckton arrived at Uralla, that Monckton falsely identified the body as that of Fred Ward, and that the police illegally discharged him from the remainder of his sentence as a consequence, intimating that this discharge was authorised as a "payment" for identifying Ward (see below):[5]

In fact, the magistrate had already identified the dead bushranger as Fred Ward long before Monckton arrived, and Monckton merely added to the evidence already collected. Moreover, no "Thunderbolt" – Fred or otherwise – received the above-mentioned injury to the right knee (a claim made in the above "Inquest" web-page that, notably, contains no substantiation). And William Monckton was a free man when he stepped off the coach, having been discharged from gaol some time previously with the remainder of his sentence remitted (see What did William Monckton actually say?).

So why are such erroneous claims being made? The author of the "Inquest" web-page is also the co-author of Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges, which declares that the bushranger shot at Uralla was not Fred Ward and that the police conspired to cover up the truth, a cover-up that continues even today. Significantly, however, the book's cataloguing classification states that it is "historical fiction", which means that it is a product of the authors' imaginations. While they try to claim that it is "based on fact", the historical evidence proves otherwise.

Indeed, the historical evidence proves that the bushranger who died near Uralla on 25 May 1870 was none other than Fred Ward.

So why are such erroneous claims being made? The author of the "Inquest" web-page is also the co-author of Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges, which declares that the bushranger shot at Uralla was not Fred Ward and that the police conspired to cover up the truth, a cover-up that continues even today. Significantly, however, the book's cataloguing classification states that it is "historical fiction", which means that it is a product of the authors' imaginations. While they try to claim that it is "based on fact", the historical evidence proves otherwise.

Indeed, the historical evidence proves that the bushranger who died near Uralla on 25 May 1870 was none other than Fred Ward.

Sources

[1] Sydney Morning Herald 1 Jun 1870 p.5

[2] NSW Police Gazette 1863 p.279

[3] Ball's presence on Cockatoo Island when Fred Ward was stationed there is confirmed by independent evidence; see Sydney Morning Herald 1 Nov 1861 p.8

[4] NSW Police Gazette 1870 p.148

[5] Inquest on Thunderbolt, 26th May 1870, by Barry Sinclair - sighted 19 Jun 2011

[http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Thunderbolt%20Inquest.html]

[1] Sydney Morning Herald 1 Jun 1870 p.5

[2] NSW Police Gazette 1863 p.279

[3] Ball's presence on Cockatoo Island when Fred Ward was stationed there is confirmed by independent evidence; see Sydney Morning Herald 1 Nov 1861 p.8

[4] NSW Police Gazette 1870 p.148

[5] Inquest on Thunderbolt, 26th May 1870, by Barry Sinclair - sighted 19 Jun 2011

[http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Thunderbolt%20Inquest.html]