Barry Sinclair's letter to the North West Magazine

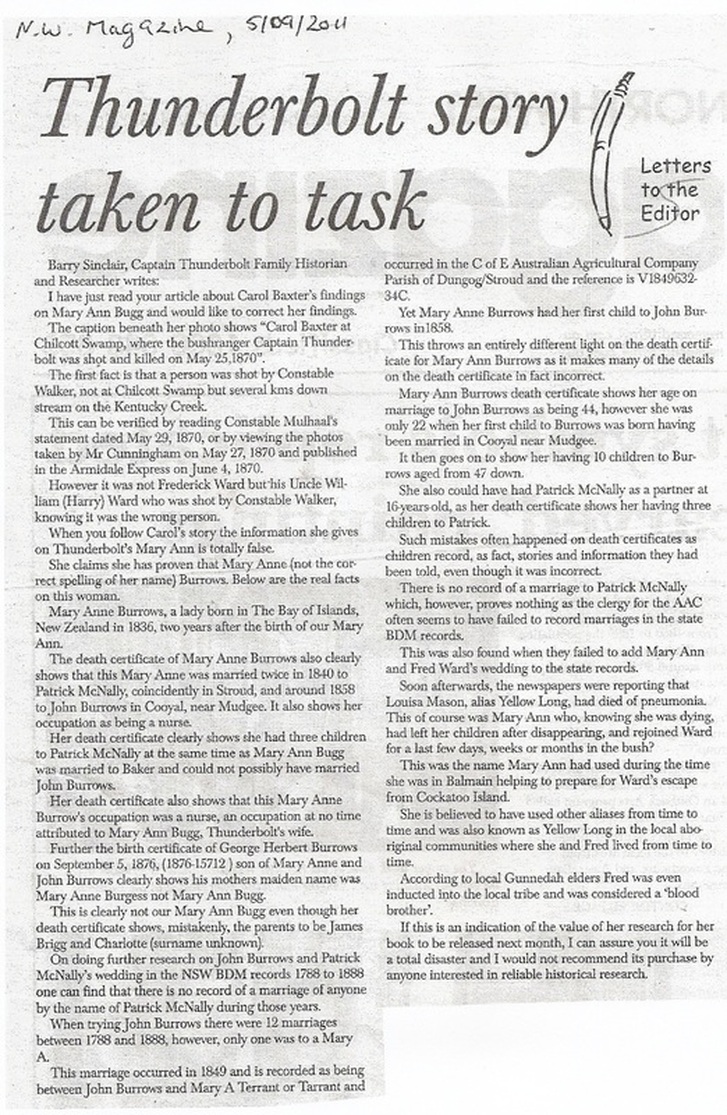

Below is a letter written to the North West Magazine by Thunderbolt aficionado Barry Sinclair claiming that my research regarding Mary Ann Bugg is "totally false". Excerpts from his letter and my responses are shown underneath.

Sinclair's letter was identical (except for the last paragraph) to one published in the Armidale Express. You can access my published response to that letter when you click here.

Excerpt: Photo caption shows "Carol Baxter at Chilcott Swamp where the bushranger Fred Ward was shot and killed on May 25, 1870. [He] was shot by Constable Walker not at Chilcott Swamp but several kms downstream at Kentucky Creek."

Response: Press error. The picture, taken when I visited Fred's death site at Kentucky Creek, showed Chilcott behind me, but when the press office wrote the caption they stated that Chilcott was where Fred died. NB. Original records noted that Fred and his pursuer "pulled up alongside a waterhole in Kentucky Creek near the junction of Chilcott's Swamp" (Armidale Express 28 May 1870).

Excerpt: "The photos taken by Mr Cunningham were published in the Armidale Express on 4 June 1870.

Response: No they weren't. They were published in the Armidale Express in 1920. The technology for reproducing photos in newspapers was not available in 1870 (for further comments see What actually happened at Kentucky Creek).

Excerpt: "However it was not Frederick Ward but his Uncle William (Harry) Ward who was shot by Constable Walker ..."

Response: Wrong on two counts. It was indeed Fred Ward who was shot as the evidence clearly shows (see When did Fred Ward die?). And William Ward was Fred's brother not his uncle (see Who were Fred Ward's parents?)

Excerpt: "She claims she has proven that Mary Anne (not the correct spelling of the name) Burrows." (sic)

Response: Eh? I think he is trying to say that "Mary Anne Burrows" could not be Mary Ann Bugg because her name was spelt Mary Anne. In fact, her Death Certificate records her name as Mary Ann. But spelling differences were largely irrelevant prior to the twentieth century anyway, that is, prior to widespread education and bureaucratic intrusion. They weren't something that people fussed about. Shakespeare himself is recorded as having spelt his own surname six different ways.

Excerpt: "Mary Anne Burrows, a lady born in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand in 1836, two years after the birth of our Mary Ann." (sic)

Response: Wrong again. Mary Ann Burrows was aged 70 at the time of her death on 22 April 1905 (see Death Certificate). By a simple mathematical calculation we can therefore work out that she was born between 23 April 1834 and 22 April 1835. Mary Ann Bugg was born during that exact timeframe - on 7 May 1834 (see Baptism Entry). Additionally, while Mary Ann's death certificate did indeed state that she was born in New Zealand, Mary Ann did not provide this information herself. She was dead by that time. But she did provide information about her own background in the 1876 Birth Certificate of her son George Herbert Burrows and stated that she was born at Gloucester, where Mary Ann Bugg was born.

Excerpt: "The death certificate of Mary Anne Burrows also clearly shows that this Mary Anne was married twice in 1840 to Patrick McNally, coincidentally at Stroud ..."

Response: Marrying the same man twice in the same year when she was aged 6? I don't think so. In fact, Mary Ann's Death Certificate stated that she was aged "16" when she married McNally indicating that the marriage occurred around 1850 (but they didn't actually marry - see Searching for Mary Ann Bugg's children).

Excerpt: "... and [married] around 1858 to John Burrows in Cooyal near Mudgee."

Response: Serious problem again with mathematical calculations. Mary Ann's Death Certificate said that she was aged 44 when she married John Burrows which means that she married him around 1878 (actually, she didn't marry him either but people always lied when asked for this type of information; they didn't just blithely say "oh no, we lived in sin!").

Excerpt: "Her death certificate also shows that this Mary Anne Burrow's (sic) occupation was a nurse, an occupation at no time attributed to Mary Anne Bugg, Thunderbolt's wife."

Response: No one can change occupations? I think there is confusion here as to what "nurse" meant at that time. It didn't necessarily mean three years of hospital training and working in an institution. Think instead of a nurse's aide, a paid companion for someone who was ailing or dying and needed physical care in the home. Mary Ann was aged 33 when she and Fred separated. She was aged 70 when she died. She was an enterprising woman who found work when she needed to support herself financially.

Excerpt: "Further the birth certificate of George Herbert Burrows on September 5, 1876 (1876-15712) son of Mary Anne and John Burrows clearly shows his mothers maiden name was Mary Anne Burgess not Mary Ann Bugg."

Response: Yes indeed (see Birth Certificate). But on his Marriage Certificate, George himself stated that his mother's name was Mary Ann Buggs. This confirms that Mary Ann Burrows was indeed Mary Ann Bugg (for more evidence, see When did Mary Ann Bugg die?). This also indicates that Mary Ann was hiding her identity in 1876 by using the surname Burgess (which is very similar to Bugg). Considering that she had been the paramour of a notorious bushranger, her use of an alias at that time is not at all surprising.

Excerpt: "This is clearly not our Mary Ann Bugg even though her death certificate shows, mistakenly, the parents to be James Brigg and Charlotte (surname unknown).

Response: "Mistakenly"? Why does Sinclair declare that this information is "mistaken"? Because, of course, these were the names of Mary Ann Bugg's parents - which is further evidence that Mary Ann Burrows and Mary Ann Bugg were the same person (see Was Mary Ann's surname Bugg or Brigg?).

Excerpt: "On doing further research on John Burrows and Patrick McNally's wedding in the NSW BDM records ..."

Response: A same sex marriage? Really? One can only wonder if the North West Magazine published all of this lengthy letter because they thought the errors in spelling, grammar, punctuation, sentence construction, mathematics and logic were hilarious.

Excerpt: "On doing further research ... [many paragraphs follow that essentially say that Sinclair couldn't find references to the husbands and children listed on Mary Ann Burrows' death certificate, therefore ...] This throws an entirely different light on the death certificate for Mary Ann (sic!) Burrows as it makes many of the details on the death certificate in fact incorrect."

Response: Wrong. He just failed to find these family members. I succeeded. (See Searching for Mary Ann Bugg's Children)

Excerpt: "Soon afterwards, the newspapers were reporting that Louisa Mason, alias Yellow Long, had died of pneumonia. This of course was Mary Ann who, knowing she was dying, had left her children after disappearing, and rejoined Ward for a last few days, weeks or months in the bush?" (sic)

Response: Wrong. A woman cannot give birth to a baby nine months after she dies. Louisa Mason died in November 1867 (see Did Mary Ann Bugg die in 1867?). Mary Ann gave birth to Fred's namesake son, Frederick Wordsworth Ward, in August 1868 (seeBirth Certificate and Baptism).

Excerpt: "This [Louisa Mason] was the name Mary Ann had used during the time she was in Balmain helping to prepare for Ward's escape from Cockatoo Island."

Response: Poor Mary Ann seems doomed to live forever with the name of the "other woman" wrapped round her neck. Mary Ann did not use the name Louisa Mason (see Who was Louisa Mason?). Mary Ann did not live at Balmain (she remained in Dungog). And Mary Ann did not help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island (see Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?).

Excerpt: "She is believed to have used other aliases from time to time and was also known as Yellow Long ..."

Response: Poor Mary Ann indeed. Not just the "other woman's" name, but her nickname (See Was "Yellow Long" one of Mary Ann Bugg's nicknames?).

Excerpt: "If this is an indication of the value of her research for her book ... I can assure you it will be a total disaster and I would not recommend its purchase by anyone interested in reliable historical research."

Response: The pot calling the kettle black?

In my response letter to the North West Magazine, I wrote:

I am sorry that Barry Sinclair doubts my conclusions regarding "Thunderbolt’s Lady", Mary Ann Bugg. What he did not disclose is that my research disproves his own theories, as presented in his book, Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges.

The problem with the Thunderbolt legend is that it has become so layered in folklore and fantasy that it is now extremely difficult to separate fact from fiction. In researching my book, Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady (Allen & Unwin, 2011), I went back to the original documents in order to discover the truth. In the process I found various new materials which answer questions that have long troubled historians, including irrefutable evidence that Mary Ann Bugg was not the woman known as Louise Mason who died in November 1867. In fact, I also discovered that much of the accepted information about Thunderbolt’s life – his birth, youth, entry into crime, his incarceration on Cockatoo Island and ticket-of-leave stint at Mudgee, his marriage, reconviction, escape from Cockatoo Island, and his bushranging career – has been inaccurately presented in Sinclair’s book, and in many others.

History is a democratic discipline. Everyone is welcome to have a go, and there is bound to be disagreement and contention, particularly when new research casts doubt on opinions which others have long held to be true, and in which they have a vested and determined self-interest. But there are appropriate means and standards of behaviour for debating these matters. Declaring someone else’s research to be a "total disaster" and recommending that no one read it is just mean and obstructive, and it denies the intelligence of the general public who I am sure are able to weigh up the competing versions themselves, and will make up their own minds based on the evidence and arguments presented to them (as shown, for example, in my website www.thunderboltbushranger.com.au). The evidence must speak for itself.

To date, the magazine has not published my response. Perhaps it lacked the necessary absurdities.

Response: Press error. The picture, taken when I visited Fred's death site at Kentucky Creek, showed Chilcott behind me, but when the press office wrote the caption they stated that Chilcott was where Fred died. NB. Original records noted that Fred and his pursuer "pulled up alongside a waterhole in Kentucky Creek near the junction of Chilcott's Swamp" (Armidale Express 28 May 1870).

Excerpt: "The photos taken by Mr Cunningham were published in the Armidale Express on 4 June 1870.

Response: No they weren't. They were published in the Armidale Express in 1920. The technology for reproducing photos in newspapers was not available in 1870 (for further comments see What actually happened at Kentucky Creek).

Excerpt: "However it was not Frederick Ward but his Uncle William (Harry) Ward who was shot by Constable Walker ..."

Response: Wrong on two counts. It was indeed Fred Ward who was shot as the evidence clearly shows (see When did Fred Ward die?). And William Ward was Fred's brother not his uncle (see Who were Fred Ward's parents?)

Excerpt: "She claims she has proven that Mary Anne (not the correct spelling of the name) Burrows." (sic)

Response: Eh? I think he is trying to say that "Mary Anne Burrows" could not be Mary Ann Bugg because her name was spelt Mary Anne. In fact, her Death Certificate records her name as Mary Ann. But spelling differences were largely irrelevant prior to the twentieth century anyway, that is, prior to widespread education and bureaucratic intrusion. They weren't something that people fussed about. Shakespeare himself is recorded as having spelt his own surname six different ways.

Excerpt: "Mary Anne Burrows, a lady born in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand in 1836, two years after the birth of our Mary Ann." (sic)

Response: Wrong again. Mary Ann Burrows was aged 70 at the time of her death on 22 April 1905 (see Death Certificate). By a simple mathematical calculation we can therefore work out that she was born between 23 April 1834 and 22 April 1835. Mary Ann Bugg was born during that exact timeframe - on 7 May 1834 (see Baptism Entry). Additionally, while Mary Ann's death certificate did indeed state that she was born in New Zealand, Mary Ann did not provide this information herself. She was dead by that time. But she did provide information about her own background in the 1876 Birth Certificate of her son George Herbert Burrows and stated that she was born at Gloucester, where Mary Ann Bugg was born.

Excerpt: "The death certificate of Mary Anne Burrows also clearly shows that this Mary Anne was married twice in 1840 to Patrick McNally, coincidentally at Stroud ..."

Response: Marrying the same man twice in the same year when she was aged 6? I don't think so. In fact, Mary Ann's Death Certificate stated that she was aged "16" when she married McNally indicating that the marriage occurred around 1850 (but they didn't actually marry - see Searching for Mary Ann Bugg's children).

Excerpt: "... and [married] around 1858 to John Burrows in Cooyal near Mudgee."

Response: Serious problem again with mathematical calculations. Mary Ann's Death Certificate said that she was aged 44 when she married John Burrows which means that she married him around 1878 (actually, she didn't marry him either but people always lied when asked for this type of information; they didn't just blithely say "oh no, we lived in sin!").

Excerpt: "Her death certificate also shows that this Mary Anne Burrow's (sic) occupation was a nurse, an occupation at no time attributed to Mary Anne Bugg, Thunderbolt's wife."

Response: No one can change occupations? I think there is confusion here as to what "nurse" meant at that time. It didn't necessarily mean three years of hospital training and working in an institution. Think instead of a nurse's aide, a paid companion for someone who was ailing or dying and needed physical care in the home. Mary Ann was aged 33 when she and Fred separated. She was aged 70 when she died. She was an enterprising woman who found work when she needed to support herself financially.

Excerpt: "Further the birth certificate of George Herbert Burrows on September 5, 1876 (1876-15712) son of Mary Anne and John Burrows clearly shows his mothers maiden name was Mary Anne Burgess not Mary Ann Bugg."

Response: Yes indeed (see Birth Certificate). But on his Marriage Certificate, George himself stated that his mother's name was Mary Ann Buggs. This confirms that Mary Ann Burrows was indeed Mary Ann Bugg (for more evidence, see When did Mary Ann Bugg die?). This also indicates that Mary Ann was hiding her identity in 1876 by using the surname Burgess (which is very similar to Bugg). Considering that she had been the paramour of a notorious bushranger, her use of an alias at that time is not at all surprising.

Excerpt: "This is clearly not our Mary Ann Bugg even though her death certificate shows, mistakenly, the parents to be James Brigg and Charlotte (surname unknown).

Response: "Mistakenly"? Why does Sinclair declare that this information is "mistaken"? Because, of course, these were the names of Mary Ann Bugg's parents - which is further evidence that Mary Ann Burrows and Mary Ann Bugg were the same person (see Was Mary Ann's surname Bugg or Brigg?).

Excerpt: "On doing further research on John Burrows and Patrick McNally's wedding in the NSW BDM records ..."

Response: A same sex marriage? Really? One can only wonder if the North West Magazine published all of this lengthy letter because they thought the errors in spelling, grammar, punctuation, sentence construction, mathematics and logic were hilarious.

Excerpt: "On doing further research ... [many paragraphs follow that essentially say that Sinclair couldn't find references to the husbands and children listed on Mary Ann Burrows' death certificate, therefore ...] This throws an entirely different light on the death certificate for Mary Ann (sic!) Burrows as it makes many of the details on the death certificate in fact incorrect."

Response: Wrong. He just failed to find these family members. I succeeded. (See Searching for Mary Ann Bugg's Children)

Excerpt: "Soon afterwards, the newspapers were reporting that Louisa Mason, alias Yellow Long, had died of pneumonia. This of course was Mary Ann who, knowing she was dying, had left her children after disappearing, and rejoined Ward for a last few days, weeks or months in the bush?" (sic)

Response: Wrong. A woman cannot give birth to a baby nine months after she dies. Louisa Mason died in November 1867 (see Did Mary Ann Bugg die in 1867?). Mary Ann gave birth to Fred's namesake son, Frederick Wordsworth Ward, in August 1868 (seeBirth Certificate and Baptism).

Excerpt: "This [Louisa Mason] was the name Mary Ann had used during the time she was in Balmain helping to prepare for Ward's escape from Cockatoo Island."

Response: Poor Mary Ann seems doomed to live forever with the name of the "other woman" wrapped round her neck. Mary Ann did not use the name Louisa Mason (see Who was Louisa Mason?). Mary Ann did not live at Balmain (she remained in Dungog). And Mary Ann did not help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island (see Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?).

Excerpt: "She is believed to have used other aliases from time to time and was also known as Yellow Long ..."

Response: Poor Mary Ann indeed. Not just the "other woman's" name, but her nickname (See Was "Yellow Long" one of Mary Ann Bugg's nicknames?).

Excerpt: "If this is an indication of the value of her research for her book ... I can assure you it will be a total disaster and I would not recommend its purchase by anyone interested in reliable historical research."

Response: The pot calling the kettle black?

In my response letter to the North West Magazine, I wrote:

I am sorry that Barry Sinclair doubts my conclusions regarding "Thunderbolt’s Lady", Mary Ann Bugg. What he did not disclose is that my research disproves his own theories, as presented in his book, Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges.

The problem with the Thunderbolt legend is that it has become so layered in folklore and fantasy that it is now extremely difficult to separate fact from fiction. In researching my book, Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady (Allen & Unwin, 2011), I went back to the original documents in order to discover the truth. In the process I found various new materials which answer questions that have long troubled historians, including irrefutable evidence that Mary Ann Bugg was not the woman known as Louise Mason who died in November 1867. In fact, I also discovered that much of the accepted information about Thunderbolt’s life – his birth, youth, entry into crime, his incarceration on Cockatoo Island and ticket-of-leave stint at Mudgee, his marriage, reconviction, escape from Cockatoo Island, and his bushranging career – has been inaccurately presented in Sinclair’s book, and in many others.

History is a democratic discipline. Everyone is welcome to have a go, and there is bound to be disagreement and contention, particularly when new research casts doubt on opinions which others have long held to be true, and in which they have a vested and determined self-interest. But there are appropriate means and standards of behaviour for debating these matters. Declaring someone else’s research to be a "total disaster" and recommending that no one read it is just mean and obstructive, and it denies the intelligence of the general public who I am sure are able to weigh up the competing versions themselves, and will make up their own minds based on the evidence and arguments presented to them (as shown, for example, in my website www.thunderboltbushranger.com.au). The evidence must speak for itself.

To date, the magazine has not published my response. Perhaps it lacked the necessary absurdities.