Analysis:

What actually happened at Kentucky Creek?

It all ended on 25 May 1870. Fred Ward stole a horse, was pursued by Constable Alexander Binning Walker and was shot to death at Kentucky Creek. He thereafter lived on as the legendary Captain Thunderbolt, the “gentleman bushranger”.

But what actually happened that day. Claims and counter claims have been made so let’s examine the actual evidence. To assist with historical transparency, full copies of long original records are provided on separate web-pages so those with an interest in the evidence can read all the details for themselves.

Giovanni Cappasotti

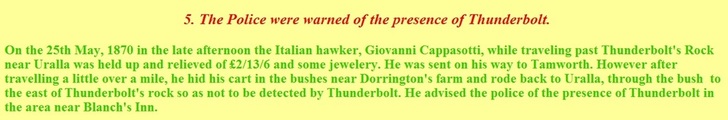

It all began mid-afternoon on 25 May 1870 when a bushranger robbed John Blanch – the innkeeper who lived near what is now called Thunderbolt's Rock – and other travellers in the same vicinity. One traveller was an Italian named Giovanni Cappasotti. After the bushranger allowed him to leave, Cappasotti travelled some distance south towards Tamworth then doubled back through the bush and alerted the Uralla police to the bushranger's activities near the Rocks.

Of this incident, one Thunderbolt website – the Fact Sheet on the Death of Thunderbolt – reports (shown below):[1]

But what actually happened that day. Claims and counter claims have been made so let’s examine the actual evidence. To assist with historical transparency, full copies of long original records are provided on separate web-pages so those with an interest in the evidence can read all the details for themselves.

Giovanni Cappasotti

It all began mid-afternoon on 25 May 1870 when a bushranger robbed John Blanch – the innkeeper who lived near what is now called Thunderbolt's Rock – and other travellers in the same vicinity. One traveller was an Italian named Giovanni Cappasotti. After the bushranger allowed him to leave, Cappasotti travelled some distance south towards Tamworth then doubled back through the bush and alerted the Uralla police to the bushranger's activities near the Rocks.

Of this incident, one Thunderbolt website – the Fact Sheet on the Death of Thunderbolt – reports (shown below):[1]

|

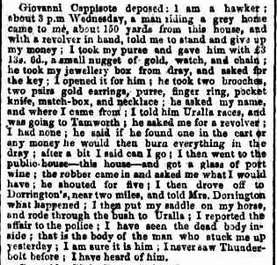

In fact, Cappasotti did not tell the police that the bushranger was "Thunderbolt", as the Fact Sheet states. Cappasotti just reported that a bushranger was robbing travellers in the vicinity of Blanch's inn. In Cappasotti's own testimony to the Magisterial Inquiry on the day after Thunderbolt's death, he stated: "I never saw Thunderbolt before. I never heard of him" (see adjacent).[7] Constable Walker reported similarly, advising his superiors that Cappasotti said to them that "he had just been stuck up by a bushranger at Blanch's and if we went quick we could catch him ... The hawker never said it was Thunderbolt."[1a]

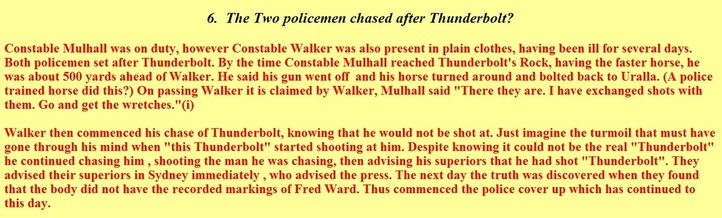

So why does the Fact Sheet state that Cappasotti told the police he had been robbed by "Thunderbolt"? As it turns out, this is part of a "government conspiracy" claim made by the Fact Sheet author in a work of fiction.[1b] The argument is that Walker knew that the bushranger shooting back at him could not be the "real Thunderbolt" because the real Thunderbolt "never shot at anyone"[1] (which itself is debunked in Did Fred Ward shoot at the police?). This enables the Fact Sheet author to claim that Walker stated that he had shot Thunderbolt when he knew he hadn't, and that in the aftermath of the news being broadcast, the police were forced to cover up the truth that Walker had actually shot someone else (see below):[1] |

|

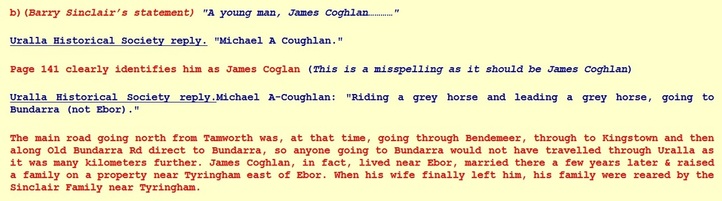

The "police cover up" claim hinges on the final statement (above) that "the next day the truth was discovered when they found that the body did not have the recorded markings of Fred Ward." In fact, at the Magisterial Inquiry the next day, multiple witnesses testified that the dead bushranger was indeed Frederick Ward based on both personal identification and the same recorded markings. The evidence is documented in the adjacent newspaper report which covers the testimony of the medical examiner at the Magisterial Inquiry, a report provided by the Special Correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald who attended the inquiry (see also When did Fred Ward die? for all the other testimonies and evidence confirming that Fred Ward was indeed the bushranger shot near Kentucky Creek in 1870).[7]

The claims regarding the police cover up begin with the false claim that Cappasotti told the police that he had been robbed by "Thunderbolt". The evidence shows that this information – and indeed the entire "government conspiracy" claim – are inaccurate. |

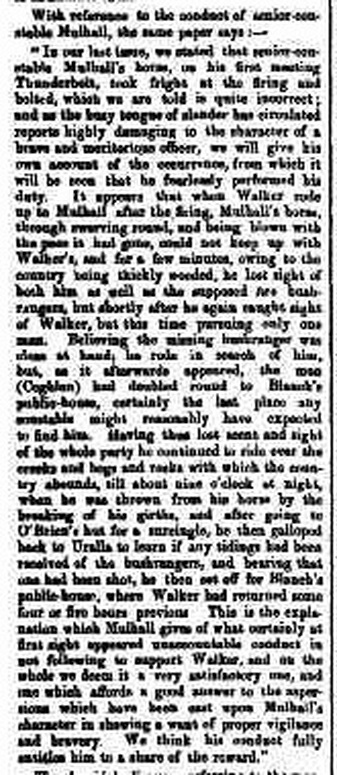

Oh, and by the way: the Fact Sheet author also claims (see above) that Mulhall said "his gun went off and his horse turned around and bolted back to Uralla". In fact, Mulhall said that the bushrangers (he believed there were two of them at the time) fired at him and he fired back (see Mulhall's Report to his police superiors as well as articles below under the heading Thunderbolt's Death).

The Fact Sheet author also questioned whether a police horse would really bolt. In truth, both the police and the police horses received minimal training. A trooper wrote in 1867 that before being sent out to enforce the law, the recruits received only two weeks of training, primarily showing them how to ride in military formation and how to salute an officer, but not how to shoot a gun![11]

The Fact Sheet author also questioned whether a police horse would really bolt. In truth, both the police and the police horses received minimal training. A trooper wrote in 1867 that before being sent out to enforce the law, the recruits received only two weeks of training, primarily showing them how to ride in military formation and how to salute an officer, but not how to shoot a gun![11]

The stolen horse

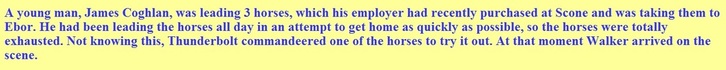

After shouting the inn's patrons with the innkeeper's takings, Fred stole a horse from a traveller. Who was that traveller?

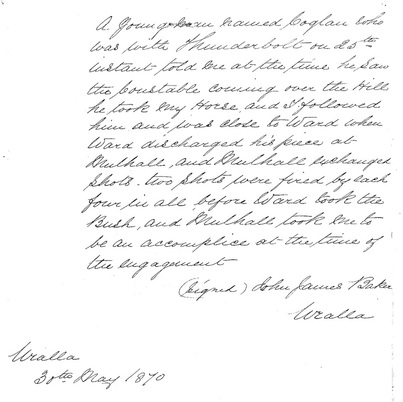

No statement from the traveller was included in the police reports sent to the Inspector General of Police on 30 May 1870 but another man, John James Baker, signed a statement on 30 May 1870 attesting to what the traveller had told him (shown below).[2]

After shouting the inn's patrons with the innkeeper's takings, Fred stole a horse from a traveller. Who was that traveller?

No statement from the traveller was included in the police reports sent to the Inspector General of Police on 30 May 1870 but another man, John James Baker, signed a statement on 30 May 1870 attesting to what the traveller had told him (shown below).[2]

While this statement did not adequately identify the man whose horse Fred stole, the man's full name – Michael A. Coughlan – is provided in a later newspaper report of cases heard before the Armidale Police Court. Coughlan charged a constable with abusive language over comments made to him in the aftermath of having his horse stolen by Thunderbolt (see Report).[3]

Strangely, this man's name has become a bone of contention with the Fact Sheet author who writes:[1]

Strangely, this man's name has become a bone of contention with the Fact Sheet author who writes:[1]

According to the Fact Sheet author's website, the Uralla Historical Society contested his claim that the man's name was James Coghlan. They provided the name of the man identified in the newspaper report of the court case (see below):[4]

History is about evidence, not belief or opinion or family stories. If a family story is correct, then documentary evidence will support the story or at least indicate that the story could be correct because of circumstantial evidence. But “family story” cannot be quoted as an irrefutable source 140 years after an event, a source to disprove all others, when documentary evidence from the time of the event records differently. History is – and must be – an evidence-based discipline.

So let's examine these claims. The Fact Sheet author says that Coghlan – he is very specific about the spelling as well as the man's given name – "lived near Ebor [and] married there a few years later and raised a family ... near Ebor". But the online indexes for the Registry of Births, Death and Marriages include no marriage entry for a James Coghlan (or Coughlan/Coughlin/Coghlin etc) who could have married in or near Ebor between 1860 and 1900, nor do they include any birth entries for children who could have been born to such a James Coghlan (or spelling variations) living in that vicinity.

That being the case, there is no evidence to support the claim that the man whose horse was stolen by Thunderbolt was named James Coghlan, or indeed anything but Michael A. Coughlan, as the report from the Police Magistrate's court states.

Distance from Uralla to Thunderbolt's Rock

In the Thunderbolt nitpicking, one subject under contention is the distance from Uralla to Thunderbolt's Rock. "For anyone who has driven along the area it is less than three miles," writes the same Fact Sheet author.[5] In fact, Google Earth measures the distance as being between six and seven kilometres (depending upon where in Uralla the end of the "ruler" is positioned). This is, of course, "as the crow flies", but Google Earth also shows that the road is almost a straight line between these two places. This equates to around four miles – a simple mathematical calculation.

Distance travelled by Constable Walker and Thunderbolt as they rode from Blanch's Inn to Kentucky Creek

The distance Walker and Thunderbolt travelled as the constable pursued the bushranger is the subject of further nitpicking. The same Fact Sheet author writes that "Walker chased Thunderbolt for approximately two miles in a south-westerly direction until they reached Kentucky Creek."[3] To those who state that the pair actually rode for six or seven miles before arriving at Kentucky Creek, the author asserts: "For anyone who has walked the distance from Blanch's Inn to the spot where the person was shot by Walker, would know that the total distance is less than 2 miles."(sic)[5]

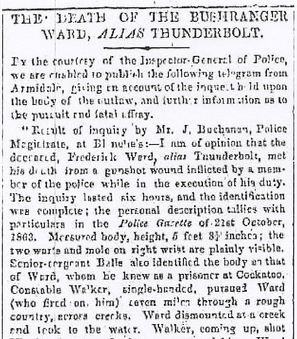

That may be the case, but Walker and Thunderbolt did not ride in a straight line – as contemporary reports make clear. The Sydney Morning Herald included a transcript of the telegram sent by the Armidale police to the Inspector General of Police after the magisterial inquiry into Thunderbolt's death; it reported that the pair travelled seven miles through rough country (below left).[6] The Sydney Morning Herald's special correspondent, who attended the magisterial inquiry on 26 May 1870 and provided the most detailed report of the inquiry, said that the race continued for more than half an hour, and that Ward "doubled like a hare", meaning that he doubled back on his tracks to fool Walker, and that Walker followed (below right).[7] The local newspapers reported similarly. In fact the Armidale Express said the chase continued for "nearly an hour" until Ward "pulled up alongside a waterhole in Kentucky Creek near the junction of Chilcott's Swamp".[8] Clearly the men followed a circuitous rather than a direct route from Blanch's Inn to Kentucky Creek so the fact that the distance from the inn to the creek is less than two miles is irrelevant.

So let's examine these claims. The Fact Sheet author says that Coghlan – he is very specific about the spelling as well as the man's given name – "lived near Ebor [and] married there a few years later and raised a family ... near Ebor". But the online indexes for the Registry of Births, Death and Marriages include no marriage entry for a James Coghlan (or Coughlan/Coughlin/Coghlin etc) who could have married in or near Ebor between 1860 and 1900, nor do they include any birth entries for children who could have been born to such a James Coghlan (or spelling variations) living in that vicinity.

That being the case, there is no evidence to support the claim that the man whose horse was stolen by Thunderbolt was named James Coghlan, or indeed anything but Michael A. Coughlan, as the report from the Police Magistrate's court states.

Distance from Uralla to Thunderbolt's Rock

In the Thunderbolt nitpicking, one subject under contention is the distance from Uralla to Thunderbolt's Rock. "For anyone who has driven along the area it is less than three miles," writes the same Fact Sheet author.[5] In fact, Google Earth measures the distance as being between six and seven kilometres (depending upon where in Uralla the end of the "ruler" is positioned). This is, of course, "as the crow flies", but Google Earth also shows that the road is almost a straight line between these two places. This equates to around four miles – a simple mathematical calculation.

Distance travelled by Constable Walker and Thunderbolt as they rode from Blanch's Inn to Kentucky Creek

The distance Walker and Thunderbolt travelled as the constable pursued the bushranger is the subject of further nitpicking. The same Fact Sheet author writes that "Walker chased Thunderbolt for approximately two miles in a south-westerly direction until they reached Kentucky Creek."[3] To those who state that the pair actually rode for six or seven miles before arriving at Kentucky Creek, the author asserts: "For anyone who has walked the distance from Blanch's Inn to the spot where the person was shot by Walker, would know that the total distance is less than 2 miles."(sic)[5]

That may be the case, but Walker and Thunderbolt did not ride in a straight line – as contemporary reports make clear. The Sydney Morning Herald included a transcript of the telegram sent by the Armidale police to the Inspector General of Police after the magisterial inquiry into Thunderbolt's death; it reported that the pair travelled seven miles through rough country (below left).[6] The Sydney Morning Herald's special correspondent, who attended the magisterial inquiry on 26 May 1870 and provided the most detailed report of the inquiry, said that the race continued for more than half an hour, and that Ward "doubled like a hare", meaning that he doubled back on his tracks to fool Walker, and that Walker followed (below right).[7] The local newspapers reported similarly. In fact the Armidale Express said the chase continued for "nearly an hour" until Ward "pulled up alongside a waterhole in Kentucky Creek near the junction of Chilcott's Swamp".[8] Clearly the men followed a circuitous rather than a direct route from Blanch's Inn to Kentucky Creek so the fact that the distance from the inn to the creek is less than two miles is irrelevant.

Kentucky Creek

The following picture of the Kentucky Creek shooting was, according to same Fact Sheet author, published in the Armidale Express on 3 June 1870.[5] The Armidale Express issues for the two weeks around Thunderbolt's shooting have not survived (evidently souvenired!) but this picture could not have been published in the Armidale Express on that date for the following reasons:

1. The Armidale Express was a weekly newspaper published on Saturdays so the date of that week's issue was 4 June;

2. The Armidale Express was a print newspaper not an illustrated newspaper;

3. Pictures in illustrated newspapers of the time were from wood-block prints not photographs. The technology for reproducing photo-graphs was either not yet available or too expensive.

The following picture of the Kentucky Creek shooting was, according to same Fact Sheet author, published in the Armidale Express on 3 June 1870.[5] The Armidale Express issues for the two weeks around Thunderbolt's shooting have not survived (evidently souvenired!) but this picture could not have been published in the Armidale Express on that date for the following reasons:

1. The Armidale Express was a weekly newspaper published on Saturdays so the date of that week's issue was 4 June;

2. The Armidale Express was a print newspaper not an illustrated newspaper;

3. Pictures in illustrated newspapers of the time were from wood-block prints not photographs. The technology for reproducing photo-graphs was either not yet available or too expensive.

The same Fact Sheet author then claims that "if the waterhole is 350 yards long" – as stated by the Sydney Morning Herald's special correspondent (above right) – "then the two men must be at least 30 feet tall".

In fact, Kentucky Creek meandered sharply at that point, as shown below in the pictures taken by Dr David Andrew Roberts in March 2011 (looking, essentially, west and north from the southerly bank which you must imagine to be a straight line). Therefore the suggestion that the photograph above shows the whole of Kentucky Creek is misleading. Moreover, the description from the Sydney Morning Herald's special correspondent is lengthy, detailed and specific – almost surprisingly so – until we note that he said "as the tracks next morning testify". This indicates that he himself travelled over the terrain the next day and determined the distances for his own report – as any able correspondent would do.

Finally, logic must come into play as well. As if Thunderbolt would jump off his horse and splash through the water if his determined pursuer could easily ride around the creek to the other side!

In fact, Kentucky Creek meandered sharply at that point, as shown below in the pictures taken by Dr David Andrew Roberts in March 2011 (looking, essentially, west and north from the southerly bank which you must imagine to be a straight line). Therefore the suggestion that the photograph above shows the whole of Kentucky Creek is misleading. Moreover, the description from the Sydney Morning Herald's special correspondent is lengthy, detailed and specific – almost surprisingly so – until we note that he said "as the tracks next morning testify". This indicates that he himself travelled over the terrain the next day and determined the distances for his own report – as any able correspondent would do.

Finally, logic must come into play as well. As if Thunderbolt would jump off his horse and splash through the water if his determined pursuer could easily ride around the creek to the other side!

Thunderbolt's death

Have you ever watched the TV drama Lie to Me? It is a fascinating insight into the "tells" that people make when they are lying – that is, their unconscious physical reactions that reflect their duplicity. Detectives have long been able to rely on another "tell". When a person recounts an incident in which they are personally involved, their story is consistent even when repeated many times over. The person might add bits of information they left out previously, or leave out bits of information they recounted previously, but the essence of the story is the same. This is because they are effectively watching a mental tape of the event so they are merely recounting what they continue to see.

Someone who is lying, however, does not have an event tape to watch. They have to rely on their memory of the story they have crafted. This is why detectives often interview suspects for long periods of time, asking them the same questions over and over again, because those who are lying are more likely to make a mistake through stress and exhaustion.

Which brings us to Thunderbolt's death. There were only two people present at Kentucky Creek that day: Ward and Walker (ignore the claims in Thunderbolt works of fiction that others were present – "fiction" means "imaginary"). As Ward died, we only have Walker’s statements as evidence. Fortunately we have more than one statement from Walker so we can assess these statements to see if they resemble each other and also resemble what others reported about the incident so as to determine whether or not his account was truthful.

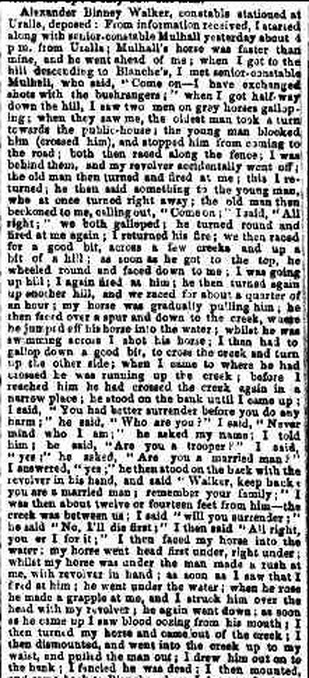

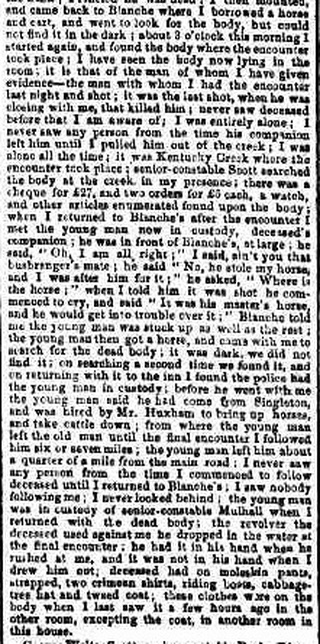

Walker testified under oath at the magisterial enquiry on 26 May 1870 and his testimony was published in detail in the Sydney Morning Herald's report by their special correspondent (shown below)[7]. Walker also provided a report for his police superiors dated 29 May (see Photocopy)[1]. The Sydney Morning Herald provided an overview of the events of that afternoon (see Photocopy). And the Armidale Express provided another two reports of the events (see Photocopy). If you read all of these reports you will note the remarkable consistency between them, a very strong indication that Walker was telling the truth.

Have you ever watched the TV drama Lie to Me? It is a fascinating insight into the "tells" that people make when they are lying – that is, their unconscious physical reactions that reflect their duplicity. Detectives have long been able to rely on another "tell". When a person recounts an incident in which they are personally involved, their story is consistent even when repeated many times over. The person might add bits of information they left out previously, or leave out bits of information they recounted previously, but the essence of the story is the same. This is because they are effectively watching a mental tape of the event so they are merely recounting what they continue to see.

Someone who is lying, however, does not have an event tape to watch. They have to rely on their memory of the story they have crafted. This is why detectives often interview suspects for long periods of time, asking them the same questions over and over again, because those who are lying are more likely to make a mistake through stress and exhaustion.

Which brings us to Thunderbolt's death. There were only two people present at Kentucky Creek that day: Ward and Walker (ignore the claims in Thunderbolt works of fiction that others were present – "fiction" means "imaginary"). As Ward died, we only have Walker’s statements as evidence. Fortunately we have more than one statement from Walker so we can assess these statements to see if they resemble each other and also resemble what others reported about the incident so as to determine whether or not his account was truthful.

Walker testified under oath at the magisterial enquiry on 26 May 1870 and his testimony was published in detail in the Sydney Morning Herald's report by their special correspondent (shown below)[7]. Walker also provided a report for his police superiors dated 29 May (see Photocopy)[1]. The Sydney Morning Herald provided an overview of the events of that afternoon (see Photocopy). And the Armidale Express provided another two reports of the events (see Photocopy). If you read all of these reports you will note the remarkable consistency between them, a very strong indication that Walker was telling the truth.

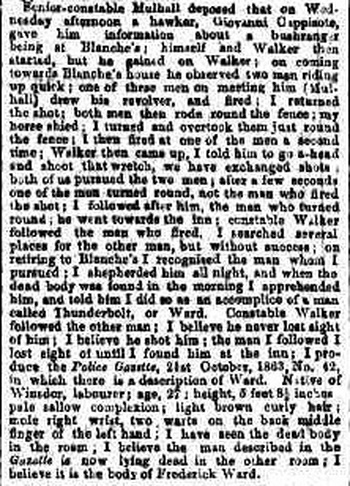

Sometimes, however, the veracity of one person's statement is only obvious when it is juxtaposed against that of another. In each of the above-mentioned reports pay close attention to the information provided by and about Senior Constable Mulhall regarding his actions on that momentous day. Then read Mulhall's testimony at the Magisterial Inquiry on 26 May 1870 (below left)[6], and his report to his police superiors dated 28 May 1870 (see Photocopy).

|

Mulhall's third statement raised even more doubts about his truthfulness. Letters to the editor of the Armidale Express in June 1870 demanded an investigation.

Yet none of the people who examined the body or visited the death site or interviewed those involved raised any questions about Walker's veracity – for obvious reasons considering the consistency in his reports. Instead, he was rewarded and promoted, and continued to be promoted, rising through the ranks of the police until he reached the role of Inspector – no small achievement for a colonial-born trooper. Recently, however, claims have been made – primarily by the Fact Sheet author, Barry Sinclair – that Walker was telling lies about what happened at Kentucky Creek that day.[3] Sinclair states: "the more reliable secondary sources basically claim 'When they returned next day they found that Ward had crawled a little distance into the bush, and was still alive, but he did not survive the trip back to Uralla… when the police examined the body and clothing they found that Ward's revolver had been empty when Walker shot and clubbed him.' (100 Australian Bushrangers, 1789-1901, Allan M Nixon.)". |

In comparing all the reports you will notice not only the remarkable consistency between Walker's reports, but the remarkable inconsistency between Mulhall's reports. Not surprisingly, the community soon began asking questions. The Armidale Telegraph reported (below):[9]

|

Yet the primary sources quoted and linked to above make it clear that Thunderbolt was dead when they found his body. Other primary sources also reveal that Thunderbolt's revolver contained a jammed bullet.[10] So Sinclair's quoted "reliable secondary source" is in fact most unreliable indeed. Even so, Sinclair has apparently used the claim that Thunderbolt was still alive the next day to call on the services of Dr Godfrey Oettle, a forensic pathologist. Oettle stated that, from the details provided at the Magisterial Inquiry by Dr Spasshatt, Thunderbolt could not have survived long: possibly losing all function within ten seconds but no doubt within minutes, depending on the extent of his injuries[3]. That's probably correct. Thunderbolt was indeed dead when they found his body the next day.

But the important question to ask is: why would Walker lie? Not only is there no evidence to suggest that he did lie (he did not even state that he had shot "Fred Ward" at the magisterial inquiry the next day, merely that he had shot a "bushranger"!), there was no reason for him to need to lie. Other witnesses could testify that the bushranger had been robbing travellers and that, when the police arrived, he had refused to put down his weapon and let himself be arrested, and that he had shot at the police. So Constable Walker had every right to take the measures necessary to bring the bushranger to account, and of course to protect himself.

Only two people were present at Kentucky Creek that day and both are now dead. All we can do is judge Walker's veracity by his actions then and in the aftermath. The evidence speaks for itself.

But the important question to ask is: why would Walker lie? Not only is there no evidence to suggest that he did lie (he did not even state that he had shot "Fred Ward" at the magisterial inquiry the next day, merely that he had shot a "bushranger"!), there was no reason for him to need to lie. Other witnesses could testify that the bushranger had been robbing travellers and that, when the police arrived, he had refused to put down his weapon and let himself be arrested, and that he had shot at the police. So Constable Walker had every right to take the measures necessary to bring the bushranger to account, and of course to protect himself.

Only two people were present at Kentucky Creek that day and both are now dead. All we can do is judge Walker's veracity by his actions then and in the aftermath. The evidence speaks for itself.

Sources:

[1] Fact Sheet on the Death of Thunderbolt [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Family%20Facts%20on%20the%20Death%20of%20Thunderbolt.html]

[1a] CSIL: Re claim for reward by Giovanni Cappasotti [SRNSW ref: 4/703 File 70/6938 No. 70/5028]

[1b] Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges by G.J. Hamilton with B. Sinclair, Phoenix Press, 2009

[2] CSIL Bushranging Medals File [SRNSW ref: 1/2326.2 File 76/2239 No. 70/4440]

[3] Armidale Express 11 Jun 1870 p.2

[4] Answers to the Uralla Historical Society comments [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Uralla%20Historical%20Society.htm]

[5] Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady - sighted 28 Sep 2011 [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Carol%20Baxter's%20Book.html]

[6] Sydney Morning Herald 28 May 1870 p.7

[7] Sydney Morning Herald 1 Jun 1870 p.5

[8] Armidale Express 28 May 1870 in Maitland Mercury 31 May 1870 p.2

[9] Armidale Telegraph in Maitland Mercury 7 Jun 1870 p.3

[10] Armidale Express 4 Jun 1870 in The Queenslander 11 Jun 1870 p.10

[11] The Empire 9 & 12 December 1867 p.2

[1] Fact Sheet on the Death of Thunderbolt [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Family%20Facts%20on%20the%20Death%20of%20Thunderbolt.html]

[1a] CSIL: Re claim for reward by Giovanni Cappasotti [SRNSW ref: 4/703 File 70/6938 No. 70/5028]

[1b] Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges by G.J. Hamilton with B. Sinclair, Phoenix Press, 2009

[2] CSIL Bushranging Medals File [SRNSW ref: 1/2326.2 File 76/2239 No. 70/4440]

[3] Armidale Express 11 Jun 1870 p.2

[4] Answers to the Uralla Historical Society comments [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Uralla%20Historical%20Society.htm]

[5] Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady - sighted 28 Sep 2011 [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Carol%20Baxter's%20Book.html]

[6] Sydney Morning Herald 28 May 1870 p.7

[7] Sydney Morning Herald 1 Jun 1870 p.5

[8] Armidale Express 28 May 1870 in Maitland Mercury 31 May 1870 p.2

[9] Armidale Telegraph in Maitland Mercury 7 Jun 1870 p.3

[10] Armidale Express 4 Jun 1870 in The Queenslander 11 Jun 1870 p.10

[11] The Empire 9 & 12 December 1867 p.2